In his short story The Canterville Ghost from 1887, Oscar Wilde wrote:

“We really have everything in common with America nowadays except, of course, language.”

Throw a few British idioms into the mix and our American friends and colleagues may be left scratching their heads and reaching for their phones.

From hundreds of British phrases, we’ve selected 20 of our favorites that have an old-fashioned quaintness.

1. A little bird told me

Meaning to receive information from a secret informant, the root source is thought to be from the Bible, Ecclesiastes 10-20:

“Do not revile the king even in your thoughts, or curse the rich in your bedroom, because a bird in the sky may carry your words, and a bird on the wing may report what you say.”

Sophie Lee’s comedy The Chapter of Accidents (1780) also uses the phrase:

“I had a little bird told me all this.”

And Shakespeare himself makes reference to it in Henry IV, Part 2:

“As far as France: I heard a bird so sing,

Whose musick, to my thinking, pleas’d the king.”

2. A turn up for the books

An unexpected stroke of good luck.

Originally “a turn up for the book”. At 18th-century horse racing meetings, punters’ names and wagers were recorded in a notebook. If an unbacked horse won, it was called a “turn up” for the bookmaker, who kept all the money.

The “luck” aspect of the phrase comes from games of chance like cribbage, where cards are “turned up” by chance.

3. A fly in the ointment

Meaning a small defect that impairs the value of something, its origins are from the Bible, Ecclesiastes 10:1 (King James Version):

“Dead flies cause the ointment of the apothecary to send forth a stinking savour: so doth a little folly him that is in reputation for wisdom and honour.”

In modern English is has come to mean something disagreeable that has come to light in a proposition, implying that there is a hidden problem.

4. A legend in one’s own lifetime

A person of considerable fame.

Originally the phrase was “a legend in her lifetime”, referring to Florence Nightingale in Giles Lytton Strachey’s book Eminent Victorians, 1918.

It spawned the humorous version “legend in one’s own lunchtime”, which means someone whose fame is fleeting.

5. A nod is as good as a wink

This 16th-century English phrase is shortened from “a nod is as good as a wink to a blind horse”.

It means that a subtle signal is sufficient to indicate agreement to undertake something borderline illegal or an understanding of sexual innuendo.

Monty Python famously played with the phrase in a sketch known as “Nudge Nudge” where Eric Idle uses the modified phrase “a nod’s as good as a wink to a blind bat”.

6. How do you do?

A greeting originating from upper-class English society and usually reserved for formal occasions today.

The response is to reciprocate with “how do you do?” as in Oscar Wilde’s Lady Windermere’s Fan, 1892:

“Lord Darlington: How do you do, Lady Windermere?

Lady Windermere: How do you do, Lord Darlington?”

It can also be used euphemistically to mean a difficult situation.

“Oh dear, this is a bit of a how do you do, isn’t it?”

7. A sight for sore eyes

A welcome or pleasing sight.

First recorded in 1738 by the Anglo-Irish satirist, essayist, and poet Jonathan Swift in A complete collection of genteel and ingenious conversation:

“The Sight of you is good for sore Eyes.”

8. For all intents and purposes

Meaning in a practical sense, or in every important respect.

Originating from English Law, it first appeared in an act adopted under Henry VIII in 1547.

“to all intents, constructions, and purposes”

It is often misheard as “for all intensive purposes”, an example of which appeared as far back as 1870 in the Indiana newspaper The Fort Wayne Daily Gazette:

“He has never had a representative in Congress nor in the State Legislature nor in any municipal office, and to all intensive purposes, politically speaking, he might have well have been dead.”

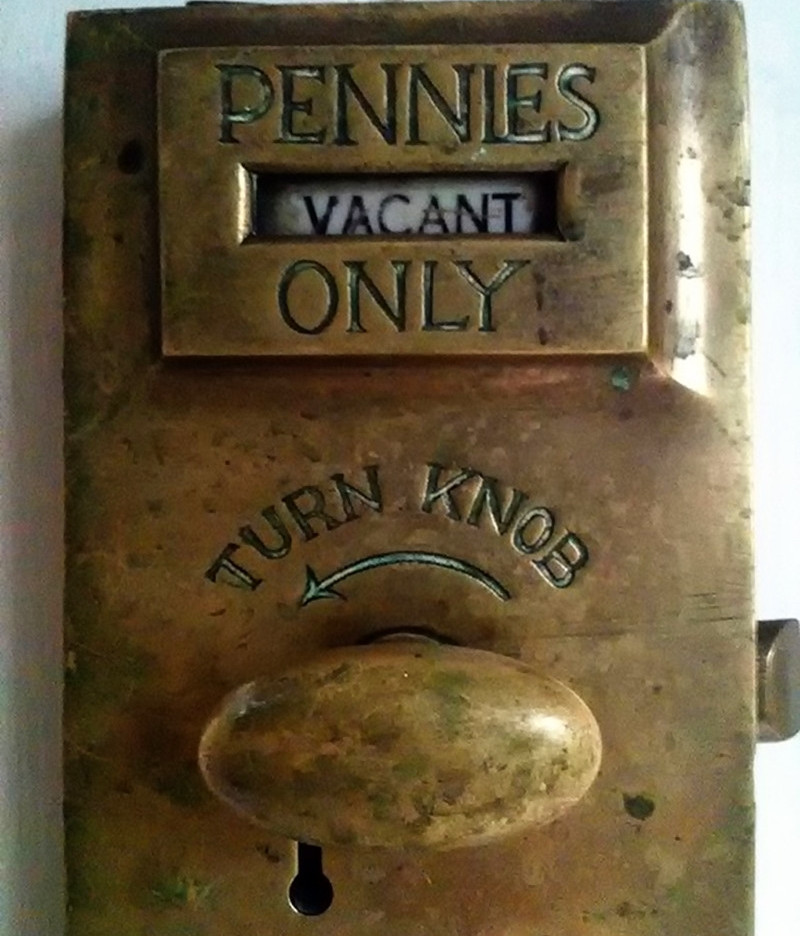

9. Spend a penny

A British euphemism for using a public lavatory.

The first modern pay lavatories in 19th-century London used a door lock that required a penny to be inserted before one could enter.

It fell out of use as a general term when the price of using the lavatory went up to 2p!

10. As keen as mustard

Means very enthusiastic, eager.

Although the first mustard factory in London, dating back to 1742, was called Keen and Sons which named their product Keen’s Mustard, there is an earlier reference to the phrase.

In 1672, “as keen as mustard” appeared in William Walker’s books Phraseologia Anglo-Latina.

Mustard has been popular as a condiment for traditional British Sunday roast beef since medieval times, although horseradish is often preferred today.

A blend of mustard and horseradish called “Tewkesbury mustard” (named after its place of origin in Tewkesbury, Gloucester) is mentioned in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, Part 2, when Falstaff says:

“He a good wit? Hang him, baboon. His wit’s as thick as Tewksbury mustard. There’s no more conceit in him than is in a mallet.”

11. A fish out of water

Someone in an unfamiliar and often uncomfortable situation.

Geoffrey Chaucer’s 14th-century collection of stories called The Canterbury Tales, revered as one of the most important works in English literature, uses what is thought to be the earliest reference to the phrase in the General Prologue:

“…a monk, when he is cloisterless;

Is like to a fish that is waterless”

12. Eat humble pie

To submissively admit one’s fault or make an apology.

In the 14th century, nobility feasting on game—especially deer—would leave the heart, liver, and entrails for the humble servants.

Known as “numbles”, which by the 15th century had become “umbles”, these leftovers were made into “umble pies”.

Samuel Pepys, a 17th-century royal administrator and member of parliament, is famous for keeping a diary for 10 years as a young man, in which he wrote:

“I having some venison given me a day or two ago, and so I had a shoulder roasted, another baked, and the umbles baked in a pie, and all very well done.”

“Mrs Turner came in and did bring us an Umble-pie hot out of her oven, extraordinarily good.”

13. Pardon my French

To excuse one’s swearing or bad language.

The origin comes from the 19th-century penchant for using French expressions in conversation and apologizing for it afterward.

Masterpiece’s new series Victoria has an example in episode 1 when Queen Victoria uses the term “au courant” to mean fashionable, but one of her ladies in waiting thinks it is the name of a hairstyle.

Another example is in The Lady’s Magazine of 1830, where “enbon-point” means plump and well-nourished.

“Bless me, how fat you are grown! – absolutely as round as a ball: – you will soon be as enbon-point (excuse my French) as your poor dear father, the major.”

14. Storm in a teacup

An over-reaction to a small or unimportant incident.

The origins probably date as far back as 52BC, with Cicero’s De Legibus which contains the Latin phrase “Excitabat fluctus in simpulo”, meaning the same as our modern day “storm in a teacup” or the American version “tempest in a teapot”.

Later versions included “a storm in a cream bowl” in 1678, a “storm in a wash-hand basin” in 1830, a “storm in a glass of water” (Dutch), and a “tempest in a potty” (Hungarian).

Scottish writer Catherine Sinclair used the first instance of the more familiar British version in 1838 in her novel Modern Accomplishments, or the march of intellect:

“As for your father’s good-humoured jests being ever taken up as a serious affair, it really is like raising a storm in a teacup”

15. Fell off the back of a lorry

For our American readers, “lorry” is the British word for “truck’. Yes, it’s a strange one.

The phrase is a euphemism for something that is acquired without payment … if you know what we mean. Nudge nudge. Wink wink.

Versions of the phrase in print don’t appear until the second half of the 20th century.

A news item in the London Times of 1968 read:

“The suggestion of the finder, a casual motorist, that the records ‘must have fallen off the back of a lorry’.”

But an earlier version using the word “truck” comes from the Australian parliamentary debate records:

“We heard, through something that had fallen off the back of a truck onto a reporter’s table.”

16. Flogging a dead horse

A fruitless attempt to get more out of something that is dead or has expired; to try to arouse interest in something that is a hopeless cause.

An 1859 printed record of a debate in the British parliament’s House of Lords is probably the earliest example of using the modern phrase:

“If the hon. Member for Birmingham had been present, he would have asked the hon. Gentleman whether he was satisfied with the results of his winter campaign. It was notorious that he was not, and a saying was attributed to him that he found he was ‘flogging a dead horse.'”

17. I’ll go to the foot of our stairs

This is an exclamation of surprise or expression of astonishment.

The phrase originated in northern England and was used extensively in Yorkshire as well as the English Midlands during the mid-twentieth century and is still used occasionally today.

It is similar to saying “stone the crows” and might be a euphemism for going to hell.

18. Gone for a burton

Referring to a person who has died or something that is broken, the origin of the term is somewhat of a mystery, but not without plausible candidates.

One is based on the English town of Burton-on-Trent in Staffordshire that brews a popular beer called Burton Ale. Britons have a habit of using humour to help deal with adversity and during the Battle of Britain in 1940, pilots who crashed into the sea were said to be “in the drink” or to have “gone for a Burton” (ale).

Another theory is about Sir Mantague Burton, who founded the British men’s clothing store called Burton in 1904. At the end of WWII, Burton supplied suits for disbanded servicemen, who were said to have “gone for a Burton” if they were absent from roll call.

19. Hanky-panky

Mischievous behaviour, dishonest or shady activity. Also a term for sexual shenanigans.

The phrase is possibly a corruption of the Romani expression hakk’ni panki, meaning “great trick” or “big con”.

First recorded in 1841 in the first edition of London’s Punch magazine:

“Only a little hanky-panky, my lud. The people likes it; they loves to be cheated before their faces.”

George Bernard Shaw uses the sexual alternative meaning in his 1939 play Geneva:

“She: No hanky panky. I am respectable; and I mean to keep respectable.

He: I pledge you my word that my intentions are completely honorable.”

20. See a man about a dog

A euphemism for excusing oneself from company whilst concealing one’s true purpose.

The 1866 play Flying Scud by Irish playwright Dion Boucicault is thought to contain the earliest known use:

“Excuse me Mr. Quail, I can’t stop; I’ve got to see a man about a dog.”

The more direct meaning was to place a bet on a dog at the races.