Rolling hills, sandy beaches, fossil cliffs, medieval towns, and moorland—the English county of Devon has it all.

Deriving its name from the ancient Dumnonii tribe of Brittonic Celts, Devon is thought to mean “deep valley dwellers”.

With so much to experience and enjoy, we’re convinced you’ll be dreaming of dwelling in Devon for your next vacation.

Landscape and Scenery

Devon is the only English county with two separate coastlines—the ruggedly beautiful rural north, with its dramatic cliffs rising 1000 ft from the sea, and the gentler rolling hills of the south, dotted with pretty towns and seaside resorts.

Lashed by the Atlantic ocean, North Devon’s coastal swells draw surfers from far and wide.

Bathed in the semi-tropical warmth carried on the Gulf Stream, South Devon experiences a milder climate, with seaside family resort towns and pretty fishing villages.

Seaside Towns and Beaches

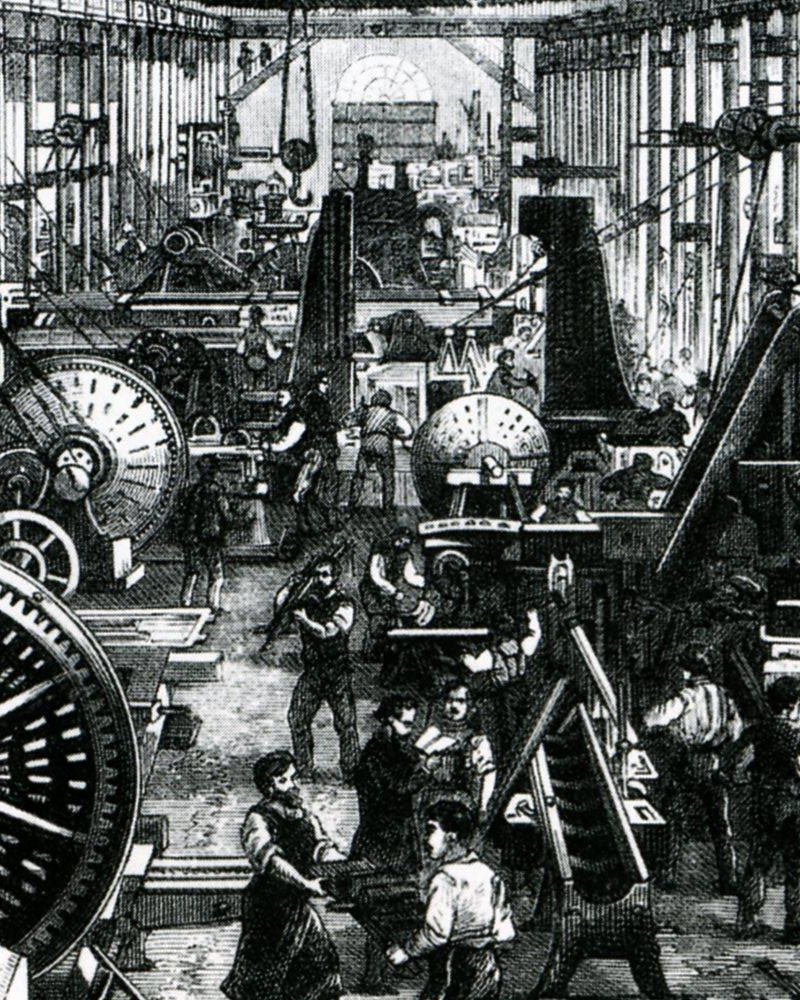

The opening of Britain’s railways during the Victorian Era enabled ordinary folk to travel to seaside resorts all across Britain.

Comparing well with the French Riviera, Victorians began calling the outstanding 22-mile stretch of coastline centered on Torbay the “English Riviera”, and the name stuck.

With its picturesque harbours, bustling towns, and family-friendly beaches, the English Riviera is perfect for either a day trip or a longer stay.

Captivated by the beauty of the Georgian town of Sidmouth, the Poet Laureate John Betjeman called it “a town caught in a timeless charm”.

Family fun and happy childhood memories are what a holiday in Devon is all about.

National Parks

Encompassing two National Parks, two World Heritage Sites, and five Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB), over half of Devon’s land is protected by law.

Known for its rounded boulder-like outcrops of granite called tors, over 160 hills include the word “tor” in their name.

Hardy, and with excellent stamina and a kind temperament, Dartmoor ponies have lived in the south west of England for hundreds of years.

Used as a working animal by local quarries and tin mines, their numbers have fallen from around 25,000 in the 1930s to a few thousand today.

Inspiring Britain’s writers for centuries, Devon has featured in many famous works, including Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby, Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, RD Blackmore’s Lorna Doone, Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies, and a host of Agatha Christie murder mysteries.

Wild and windswept, Dartmoor soaks up the warmth of the setting sun.

Cathedrals, Abbeys, and Churches

Completed in around 1400 and dedicated to Saint Peter, Exeter Cathedral’s Decorated Gothic style replaced a much earlier Norman design, of which two massive towers remain.

Constructed entirely of local stone, notable features include the multi-ribbed ceiling, the Great East Window containing 14th-century stained glass, and Britain’s earliest complete set of fifty misericords (wooden carvings on seats designed to fold up and act as support during standing prayer).

Exeter Cathedral has the longest uninterrupted vaulted ceiling in the world, at about 315 ft.

Buckfast Abbey is an active Benedictine monastery that was refounded in 1882 after the previous 12th-century abbey was destroyed during King Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1539.

Dedicated to the Anglo-Saxon princess Werburgh, the parish church at Wembury, in the hills above the beach, has commanding views across the South Devon Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

There are literally dozens of historically significant village churches to explore, many dating from Norman Britain.

Named after a Roman centurion who converted to Christianity, the parish church at Tavistock is a “wool church”—financed primarily by rich wool merchants and farmers during the Middle Ages, hoping their largesse would ensure a place in heaven.

Castles and Country Houses

Powderham Castle is a fortified manor house and home to the Courtenay family, Earls of Devon.

The appellation “castle” was added in the 17th century and although never a true castle with a keep and moat, it had a protective curtain wall and yard on the east side.

Featuring a mixture of medieval towers and fine 18th-century decoration, Powderham Castle is named from the ancient Dutch word “polder”, and means “the hamlet of the reclaimed marsh-land”.

The Staircase Hall has an impressive mahogany staircase decorated with carved heraldic beasts and intricate plasterwork.

Used as the filming location for the highly-rated 1983 version of Conan Doyle’s “The Hound of the Baskervilles”, Knightshayes Court is pure Victorian Gothic, complete with gargoyles, corbels, and a medieval-inspired great hall.

Renowned architectural scholar Nikolaus Pevsner called it “an eloquent expression of High Victorian ideals in a country house”.

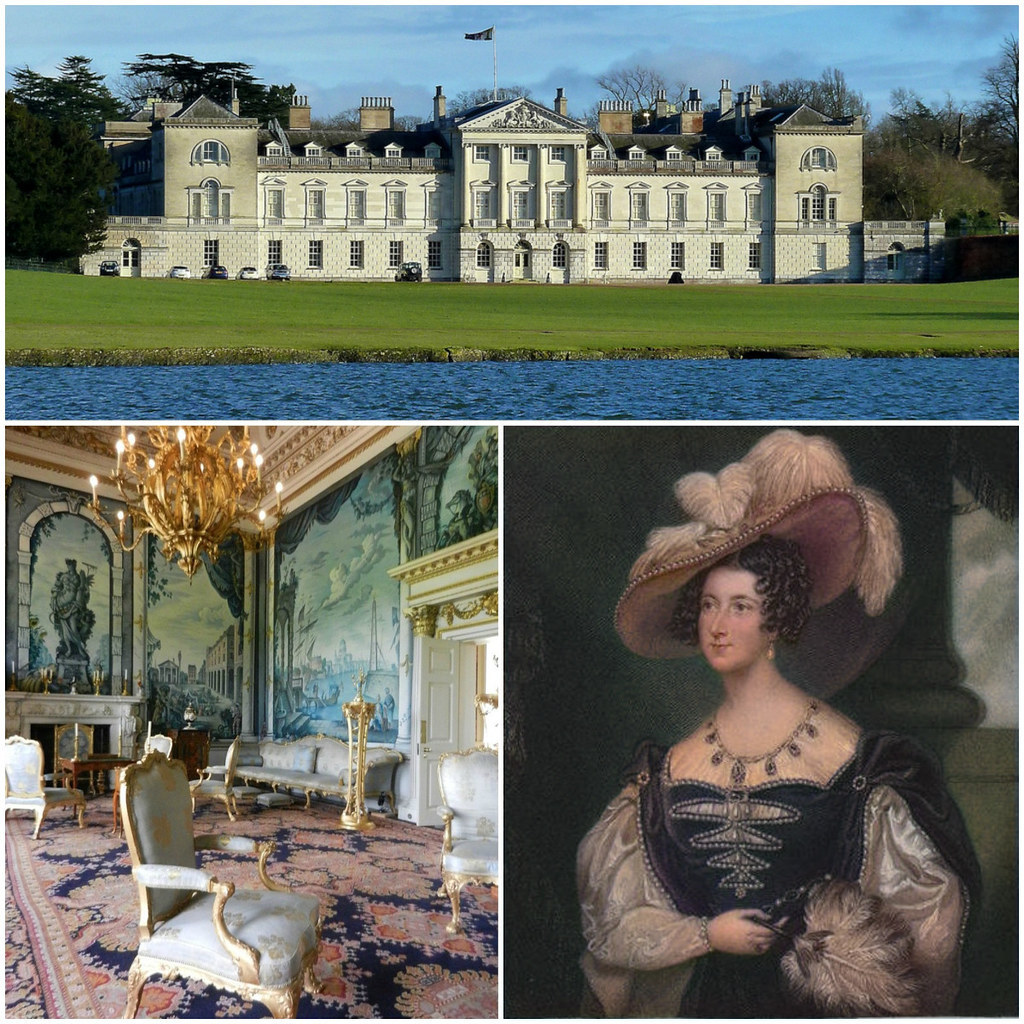

Designed by Scottish neoclassical architect Robert Adam, the beautiful Georgian mansion of Saltram House was described by architectural scholar Pevsner as “the most impressive country house in Devon”.

Considered one of Adam’s finest interiors, the sumptuous drawing room features Rococo plasterwork, exceptional paintings, luxurious Axminster carpets, and the finest damask upholstered Thomas Chippendale furniture.

Devonshire Cream Tea

Derived from Devon county, the term “Devonshire Cream Tea” refers to a light meal taken in the afternoon at around 4 pm, consisting of a pot of tea with scones, clotted cream, and jam.

Anglo-Saxon texts from around the 8th century refer to “Defenascir”, meaning “Devonshire” after it changed from the Latin name “Dumnonia” following the fall of Roman rule in Britain.

Devon and Cornwall have different ideas over how to eat scones with cream tea.

Devonians prefer to add cream first followed by jam, whereas the Cornish way is to add the jam first.

Either way, Devonshire Cream Tea remains one of the most popular snacks ordered at countless tea shops and cafes in the region and across Britain.

Dairy farming has been important to Devon for centuries, with the 11th-century monks at Tavistock Abbey known to have offered bread with cream and jam to local workers who helped rebuild the Abbey after it was attacked by Vikings in 997 AD.

Related post: 8 Surprising Facts About British Tea Traditions

The best cream comes from happy cows, and Devon’s cows are among the happiest—churning out cream by the churnful!

Watersmeet House is a beautiful former fishing lodge turned into a tea room and shop by the National Trust.

Surrounded by pristine countryside, it makes a perfect place to stop for afternoon tea for the whole family.

The 18th-century 16-sided “A La Ronde” is a licensed award-winning tea-room offering delicious homemade cakes, afternoon tea, and light meals.

Sourced from local farms, specialties include the smoked chicken, the South Devon sweet chilli jam and, of course, the Devonshire clotted cream.

Eat inside the tea-room or out on the lawn taking in the estuary views with picnic rugs provided.

Coastal Walks

Stretching for 630 miles along the coasts of Devon, Cornwall, Somerset, and Dorset, the South West Coast Path is England’s longest waymarked footpath and National Trail.

Originating as a path for coastguards to walk between lighthouses while patrolling for smugglers, the South West Coast Path covers both the north and south coasts of Devon.

Pretty Villages and Towns

Devon is dotted with dozens of pretty coastal and inland villages and towns.

Brightly-coloured fishing villages and quaint thatched cottages typify the beautiful settings—perfect for strolling among antique and gift shops, bookstores, and galleries.

Step back in time in the beautiful seaside village of Clovelly on Devon’s north coast.

Flanked by whitewashed houses—most of which are architecturally listed and protected as historically important—Clovelly’s steep cobbled main street descends 400 ft to the harbour below.

Dating back to 907 AD, Totnes was a thriving market town with many wealthy merchant’s houses from the 16th and 17th centuries lining the “Fore Street”—the name given to the main thoroughfare in many towns of south west England.

Operating over part of a converted railway branch line, the Tramway in the little seaside town of Seaton runs 13 half-scale replicas of classic British trams on a 3-mile route through East Devon’s beautiful Axe Valley.

With so much to offer, Devon is sure to have you dreaming of your next visit.