Nestled in the southwest corner of England, Somerset is a county woven from rolling green hills, dramatic coastlines, and ancient history. Its very name whispers of its Saxon roots, derived from “Sumorsæte”—meaning “summer people”—hinting at the sunshine hours that bathe its golden stone villages and lush meadows.

Explore Somerset, a place where time itself seems to slow, inviting you to savour the beauty and rich heritage of this captivating English county.

1. Historic Sites: A Journey Through Time

History comes alive in Somerset with its numerous historical landmarks, each whispering tales of the past.

The Roman Baths in Bath, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, offer a glimpse into Roman life in Britain, showcasing the well-preserved bathing complex and intricate architecture.

Beyond its Roman roots, Bath boasts a remarkable city centre adorned in the elegant style of Georgian architecture. Think sweeping crescents, grand terraces, and honey-colored Bath stone, all meticulously planned and executed during the 18th century.

The elegant Palladian Bridge at Prior Park, inspired by the work of 16th-century Venetian architect Andrea Palladia, is one of only four remaining in the world.

Overlooking the River Avon near Pulteney Bridge, a curious Queen Anne Revival building, originally the Empire Hotel, and now luxurious flats, boasts a roofline designed with a social commentary in mind.

Completed in 1901, the architect envisioned the roof as a symbol of social mobility. A grand, castle-like section on the left represented the wealthy, while a Dutch-gabled house in the center signified the middle class. Finally, a charming cottage on the right embodied the working class.

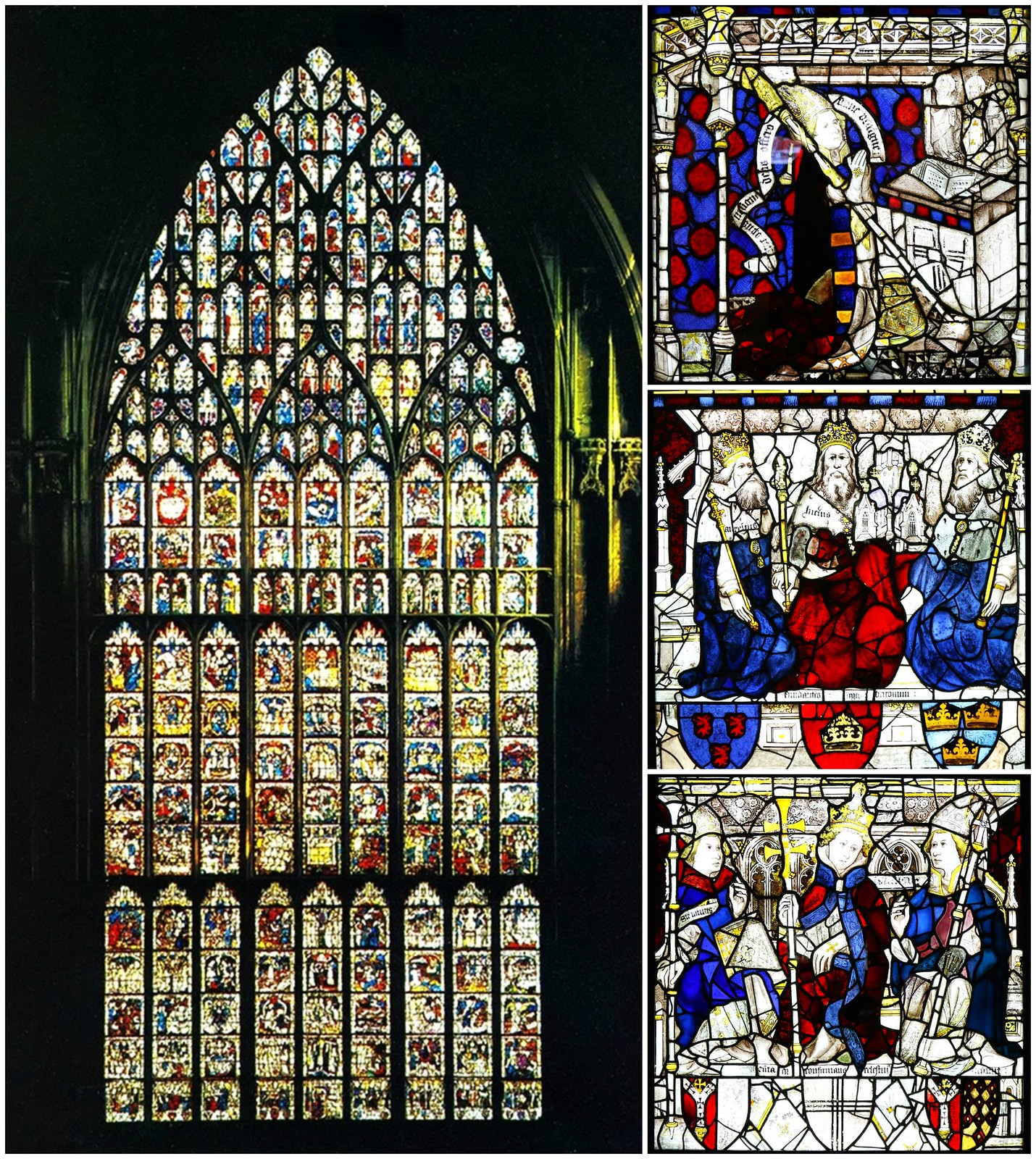

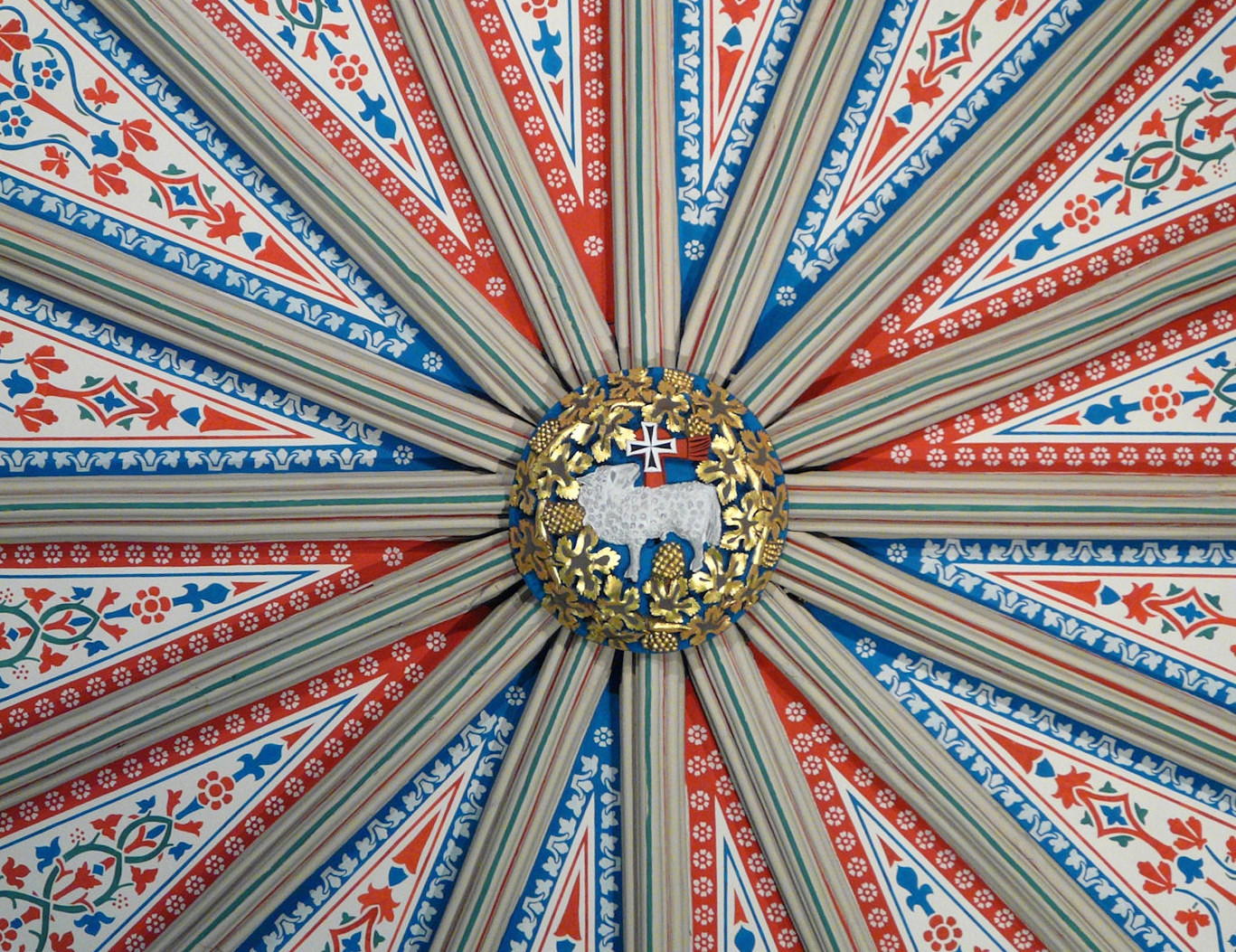

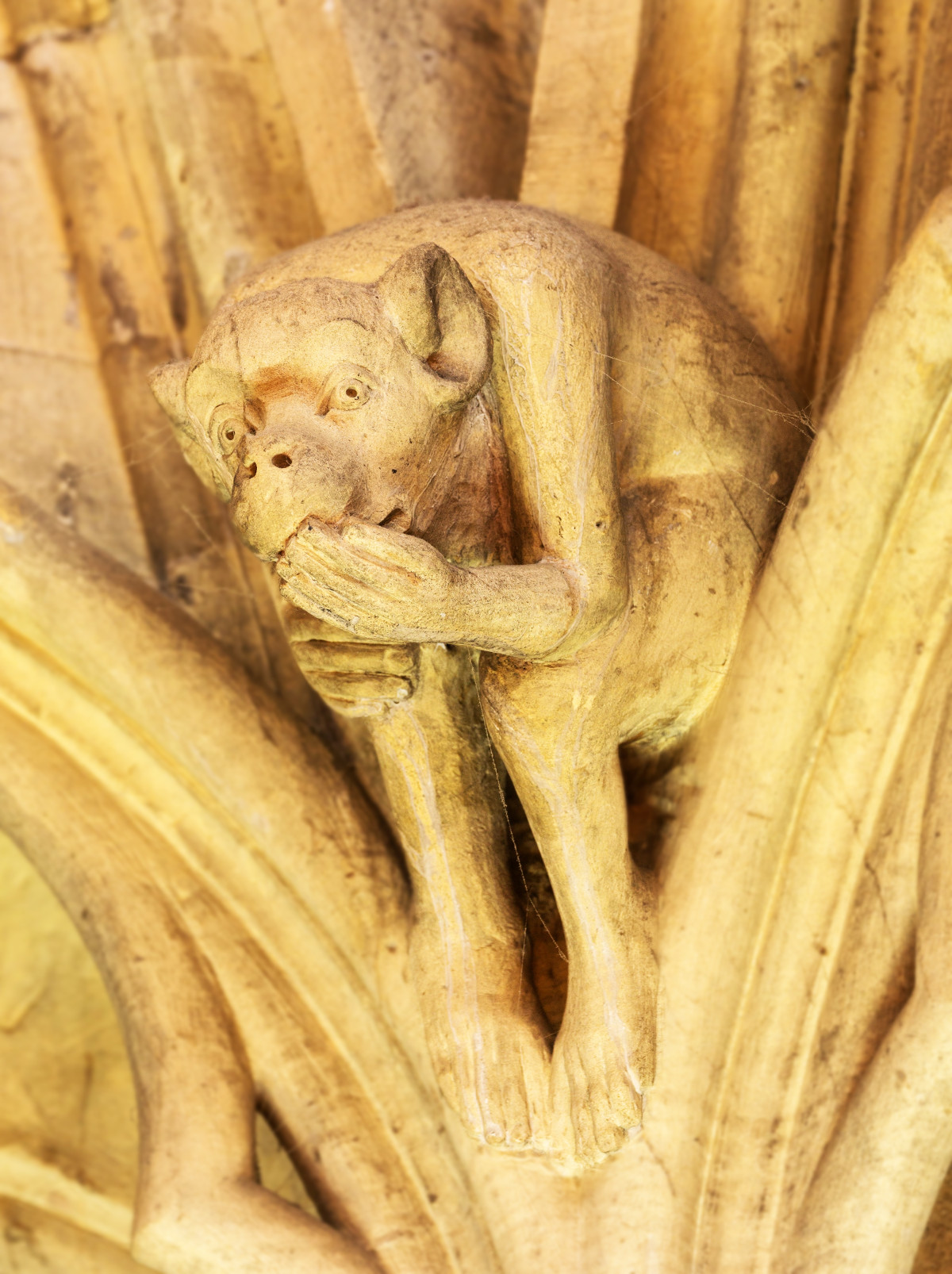

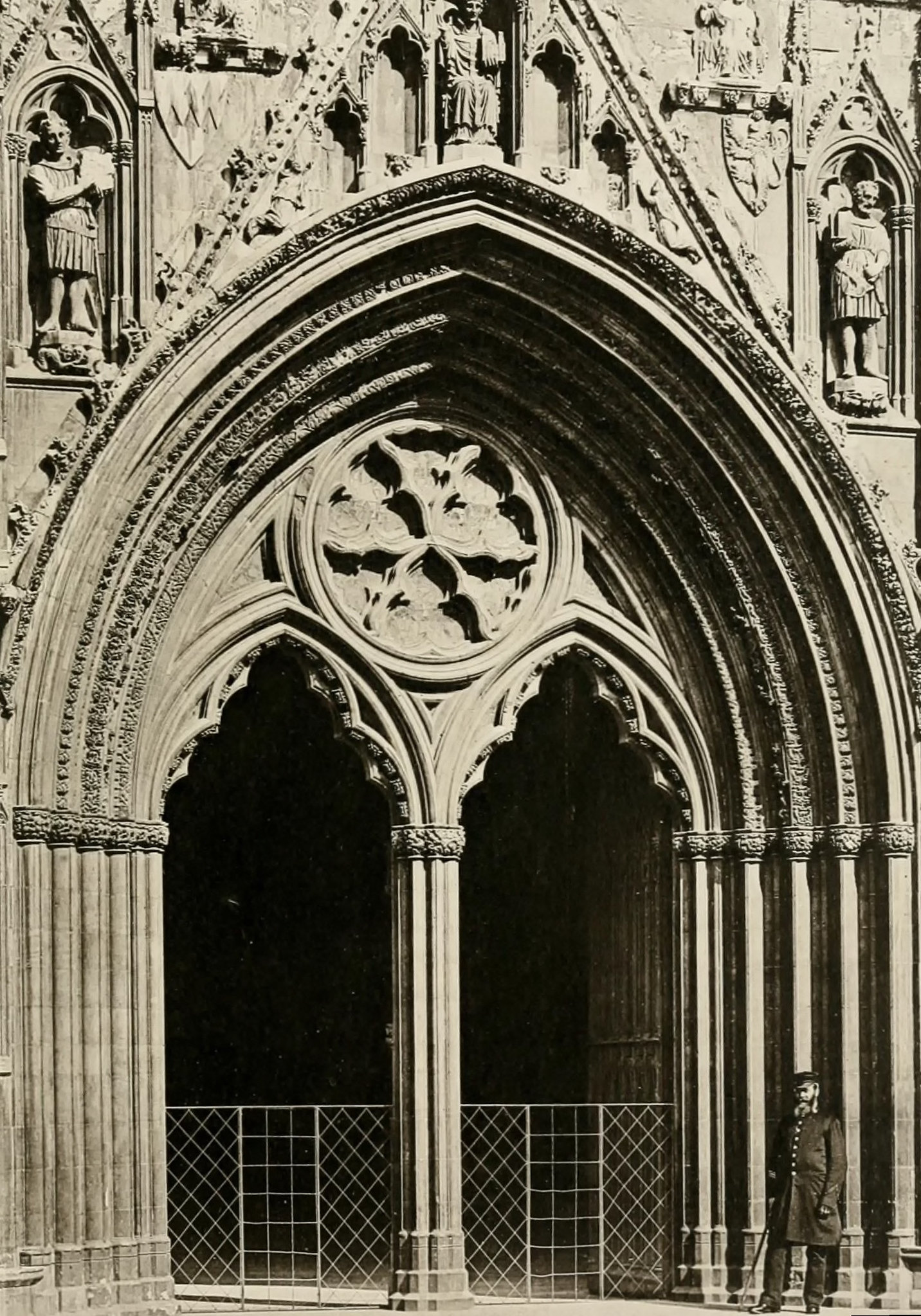

The city of Wells, named after three holy wells dedicated to Saint Andrew and once believed to have curative powers, boasts a magnificent cathedral, charming medieval streets, and a vibrant market square.

Vicars’ Close, in Wells, is said to be the oldest residential street in Europe with original buildings all surviving intact.

The ruins of Glastonbury Abbey, once one of the wealthiest and most powerful monasteries in medieval England, stand as a testament to Somerset’s rich religious past.

Glastonbury Tor, a mystical hill rising from the Somerset plains, boasts a history as abundant as its legends. For millennia, it was likely a site of pagan worship.

Myths have swirled around Glastonbury Tor, connecting it with Avalon—the mythical Isle of the Dead—and King Arthur’s fabled resting place. Some even claim it holds the secret of the Holy Grail. Atop the Tor, the imposing tower, a vestige of a medieval church, stands as a tangible connection to this timeless legacy

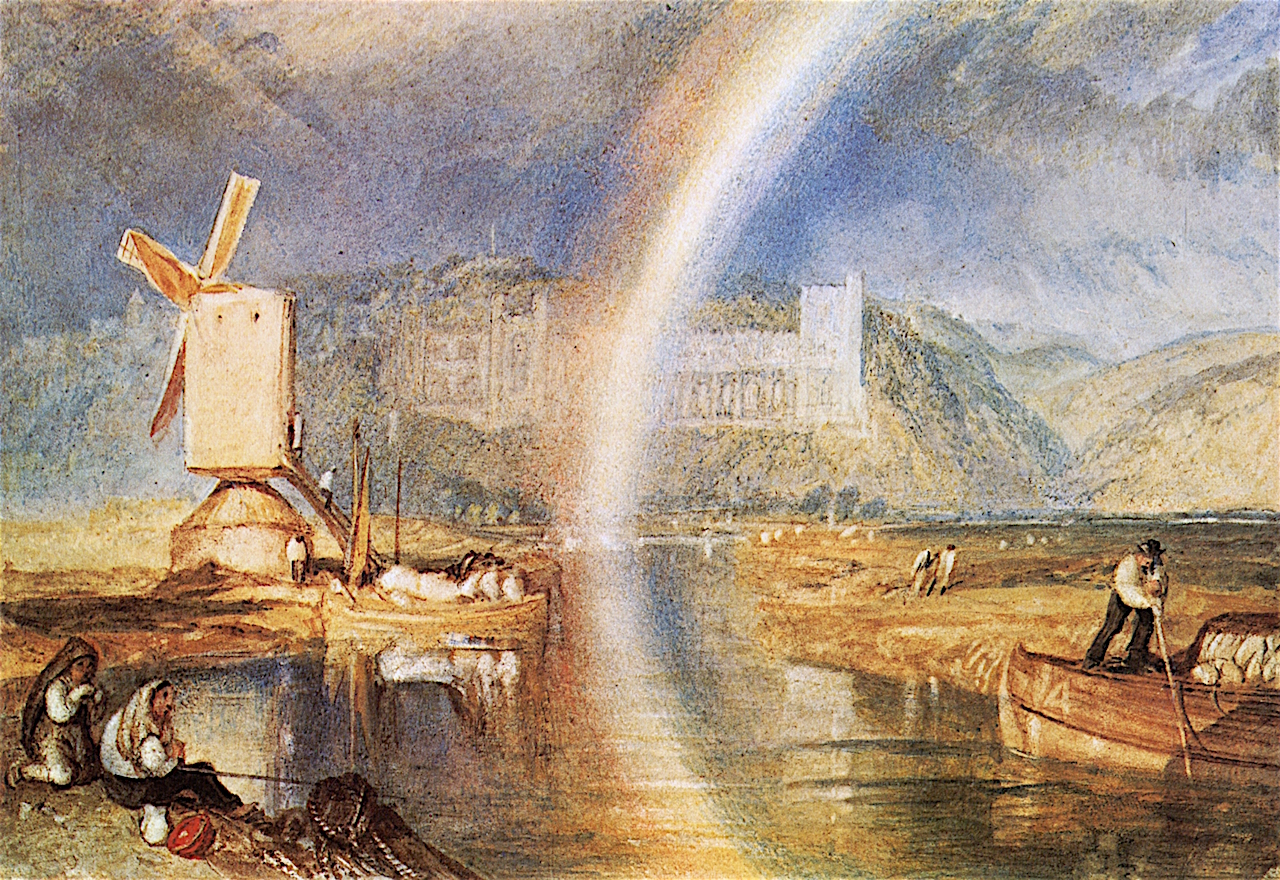

Centuries ago, when tales of King Arthur painted the land, the River Brue overflowed, forming a vast lake south of Glastonbury Tor. Legend has it, that it was here, near the Pomparles Bridge at the western end of the lake, that Sir Bedivere, under orders from the mortally wounded king, finally returned the sword Excalibur to the Lady of the Lake.

The terraces around the Tor, called “lynchets” date from the middle ages and are thought to have been man-made to maximize land use for agriculture, although they may have served a ceremonial purpose.

Towering over the village of Dunster on the edge of Exmoor National Park, Dunster Castle provides a glimpse into medieval warfare and aristocratic life, with its impressive fortifications and well-preserved interiors.

Embodying the elegance of the Elizabethan Renaissance, Montacute House stands as a testament to the era’s artistry. Towering glass walls and glowing hamstone—a honey-coloured building stone from nearby Ham Hill—combine seamlessly with its surrounding garden, creating a masterpiece of enduring historical importance.

From Roman settlements to medieval castles and religious landmarks, Somerset offers a fascinating journey through history, allowing visitors to connect with the past and appreciate its enduring legacy.

2. Charming Towns and Villages: Exploring Somerset’s Soul

Somerset’s charm extends beyond its natural beauty and historical significance. The county is dotted with numerous captivating towns and villages, each with its unique character and story to tell.

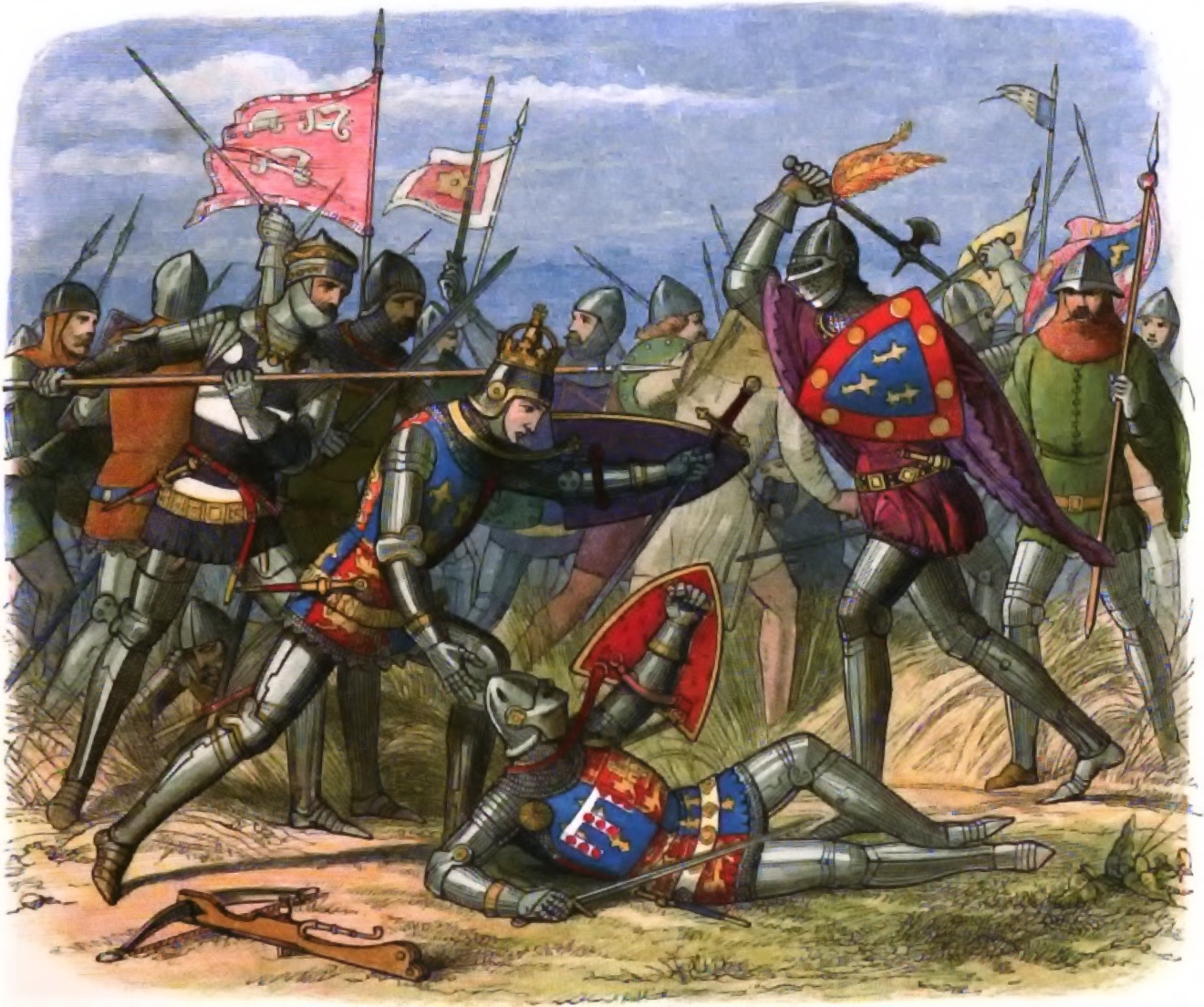

Steeped in history, the village of Norton St Philip witnessed the bloody clash of the Monmouth Rebellion in 1685—an uprising against King James II.

One of Britain’s oldest taverns, the 14th-century timber-framed George Inn was once part of a stage coach route from London and has been offering weary travellers a delicious hot meal, craft ales, and cozy accommodations for centuries.

Nestled in the Cotswolds Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, the idyllic village of Freshford offers a glimpse into a timeless England with its honey-colored cottages and charming riverside setting.

Well worth a visit, the nearby Iford Manor sits on the border of Somerset and Wiltshire and offers stunning Italianate gardens and three miles of nature walks. Iford was rated one of the most beautiful villages in the UK and Ireland by Condé Nast Traveller magazine.

The tiny hamlet of Friary offers a peaceful atmosphere with a handful of cottages nestled beside the River Frome.

A blend of history and nature, Pensford village charms visitors with its designated Conservation Area status, showcasing its well-preserved architecture alongside the scenic beauty of the Chew Valley. The village’s crown jewel is the unique St Thomas à Becket Church, standing proudly on an island amidst the River Chew.

For a town so steeped in legend and mysticism, it’s hardly surprising that intertwined within Glastonbury’s charming streets, you’ll find uniquely quirky shops catering to New Age lifestyles and spiritual enquiry, peppered with lots of independent cafes, pubs, and restaurants.

Nestled beneath the majestic Mendip Hills, Axbridge is a charming market town where half-timbered buildings line narrow streets leading to a medieval market square. Dating back to the reign of King Alfred, the town played a key role in defending against Viking invaders.

Built as a Methodist Church and later used as a Masonic Lodge, the late 19th-century Rickford Chapel’s distinctive timber-framing and pyramidal tower roof lend a picturesque charm to the little hamlet of Rickford.

Frome, known for its creative spirit, is a haven for independent shops, art galleries, and cafes.

Quiet Hinton Charterhouse hides a surprising past. In the 13th century, Carthusian monks seeking solitude built a monastery there, abandoning their earlier location because it was too noisy!

Thatched cottages are a quintessential part of Somerset’s charm. These beautiful dwellings with their roofs of straw or reed have been a feature of the Somerset landscape for centuries. They were traditionally built using local materials and provided excellent insulation, keeping residents cool in the summer and warm in the winter.

Mells Manor is a 16th century house in the village of Mells, Somerset, that has been owned by the aristocratic Horner family since 1543.

Sir John and Lady Frances Horner lost their only surviving son and heir, Edward, at the Battle of Cambrai during Word War One.

A memorial statue stands inside St Andrew’s Church, which shares a wall with the manor house.

With charming Tudor buildings lining Fore Street in Taunton, it’s hard to imagine that this quaint market town holds the distinction of being the first town in the country to have permanent electric street lighting in 1881.

From bustling market towns to quaint villages with cobbled streets and traditional houses, Somerset offers a quintessential English experience, inviting visitors to slow down, explore, and soak in the unique atmosphere of each location.

3. Beautiful Landscapes: A Feast for the Senses

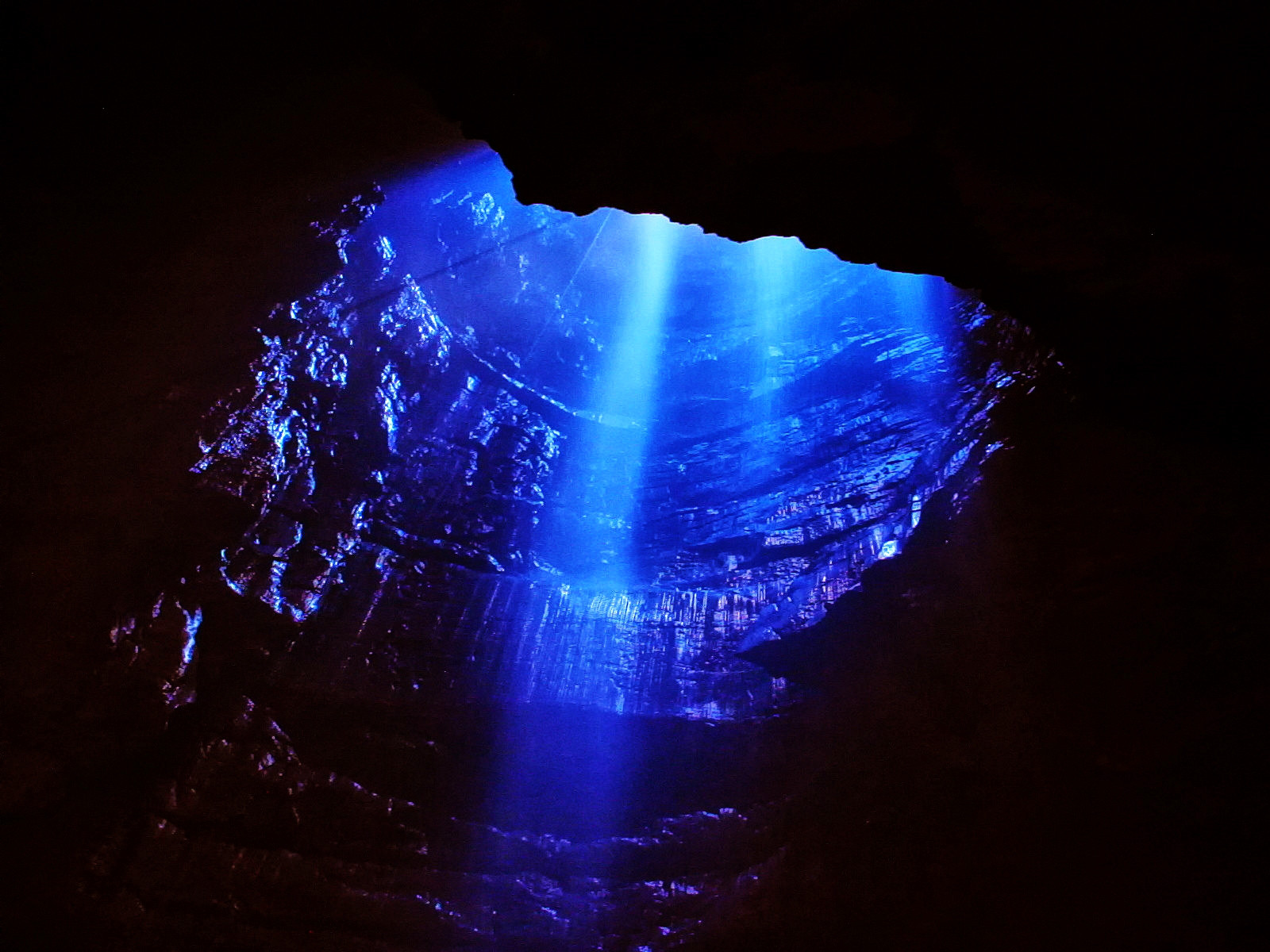

Somerset’s diverse landscape offers a breathtaking backdrop for exploration and adventure. The dramatic Cheddar Gorge, England’s largest gorge, carves through the Mendip Hills, offering stunning limestone cliffs and panoramic views.

A remarkably well-preserved human skeleton, nicknamed “Cheddar Man”, estimated to be 9,000 years old, was unearthed in the limestone caves beneath this dramatic landscape.

Along the coast, the Bristol Channel provides sandy beaches and charming seaside towns, perfect for relaxation and coastal exploration.

Whether seeking dramatic cliffs, rolling hills, or sandy beaches, Somerset’s diverse landscapes cater to every outdoor enthusiast.

4. Cheddar Cheese and Cider: A Toast to Local Tradition

Somerset’s claim to fame undoubtedly lies with its iconic Cheddar cheese. This crumbly, sharp-flavored cheese boasts a rich history dating back centuries. Legend has it that the unique cave environment in the village of Cheddar, with its constant cool temperature and high humidity, played a crucial role in developing its distinctive characteristics.

Over the years, Cheddar cheese production has evolved, with various styles and flavors emerging. Today, Somerset remains a significant producer of high-quality Cheddar cheese, adhering to strict traditional methods and regulations to ensure its authenticity and continued popularity worldwide.

Somerset’s rolling hills were once a tapestry of apple orchards, earning it the historical title of the “cider capital of the UK”. Cider, a fermented alcoholic beverage made from apples, has been a cornerstone of Somerset’s culture and economy for centuries. Local producers have perfected the art of crafting cider, using specific apple varieties and fermentation techniques to achieve unique flavors and styles.

From the dry and refreshing “scrumpy” cider to the sweeter and fruitier varieties, Somerset offers a diverse range to tantalize every taste bud. Cider plays a significant role in local celebrations and traditions, and cider houses remain popular venues for socializing and enjoying this beloved beverage.

5. Outdoor Activities and Adventures: Embracing Somerset’s Beauty

Somerset’s diverse landscapes offer a playground for outdoor enthusiasts, beckoning you to explore its hidden gems and experience the thrill of adventure.

Cruise leisurely along scenic towpaths or push your limits on demanding road and mountain bike trails – Somerset caters to cyclists of all stripes.

From heart-pounding climbs on Cheddar Gorge’s cliffs to gentler introductory scrambles, Somerset’s rock faces offer exhilarating challenges for all skill levels.

For those who prefer a more leisurely pace, the West Somerset Railway offers a scenic journey on a historic steam train along the edge of the Quantock Hills and the Bristol Channel coast.

For an even more leisurely pace, how about gliding down the scenic Kennet and Avon Canal? Breathe in the fresh air and let the tranquility of Somerset unfold before you. Fancy a cuppa along the way—no problem, just pull over and put the kettle on!

Nature lovers rejoice! From soaring birds of prey to wild ponies that roam the windswept moors, Somerset’s diverse habitats – wetlands, cliffs, rolling hills, and ancient woodlands – burst with a rich tapestry of wildlife.

With their shaggy dun coats rippling in the wind, Exmoor ponies, a hardy native breed, embody the wild spirit of Somerset’s moors. Their descendants, the Quantock Ponies, call the nearby Quantock Hills home.

From the whispers of ancient ruins to the call of the wild, Somerset weaves a spell that lingers long after your visit. Let its timeless beauty seep into your soul, and discover a place where history and nature intertwine to create a truly unforgettable experience.

The following images connect you with Amazon and contain Affiliate links, which means we may earn a small commission from qualifying purchases. Thanks for supporting our work.