On April 26, 1607, an expedition sent by the Virginia Company of London arrived at the entrance to what is now Chesapeake Bay, Virginia, in the United States.

The First Landing

Among those of the first landing party was Captain John Smith, who described the bay in his book The Generall Historie of Virginia, New England & the Summer Isles,

“The bay lyeth north and south, in which water floweth near 200 myles, and hath a channel for 140 myles; of depth, betwixt 6 and 15 fathome, holding a breadth, for the most part, 10 or 14 myles.”

No matter which side of the Atlantic you hail from, those words probably look a little alien. That’s because the settlers spoke an earlier version of English called “Early Modern English”—a kind of transitional stage between Middle English and the Modern English of today.

Early Modern English was the language of Shakespeare and the King James Bible—both highly revered, then as now, but neither offered much advice on how to negotiate with the Native American population.

Adapting to the New Landscape

So the 17th-century settlers naturally set about adapting the language to suit their new environment. Many words were borrowed from indigenous languages, either directly or through intermediate Spanish, French, and other settlers.

Describing the American flora and fauna required new words. For example, sequoias are named in honor of Sequoyah, a Cherokee leader; squash derives from Narragansett, an extinct Algonquian language formerly spoken in what is now Rhode Island; Hickory comes from the Powhatan people of Virginia, and Chipmunk originates from the Ojibwe language, once spoken in Canada and the United States from Michigan to Minnesota.

Other words came from French, Dutch, German, and Spanish: levee, portage, and gopher from French: cookie, cruller, stoop, and pit (as in fruit) from Dutch; angst, kindergarten, sauerkraut from German; barbecue, stevedore, and rodeo from Spanish.

Initially, the changes were criticized by purists on both sides of the Atlantic. But after the Revolution, Americans began to take pride in their own form of English.

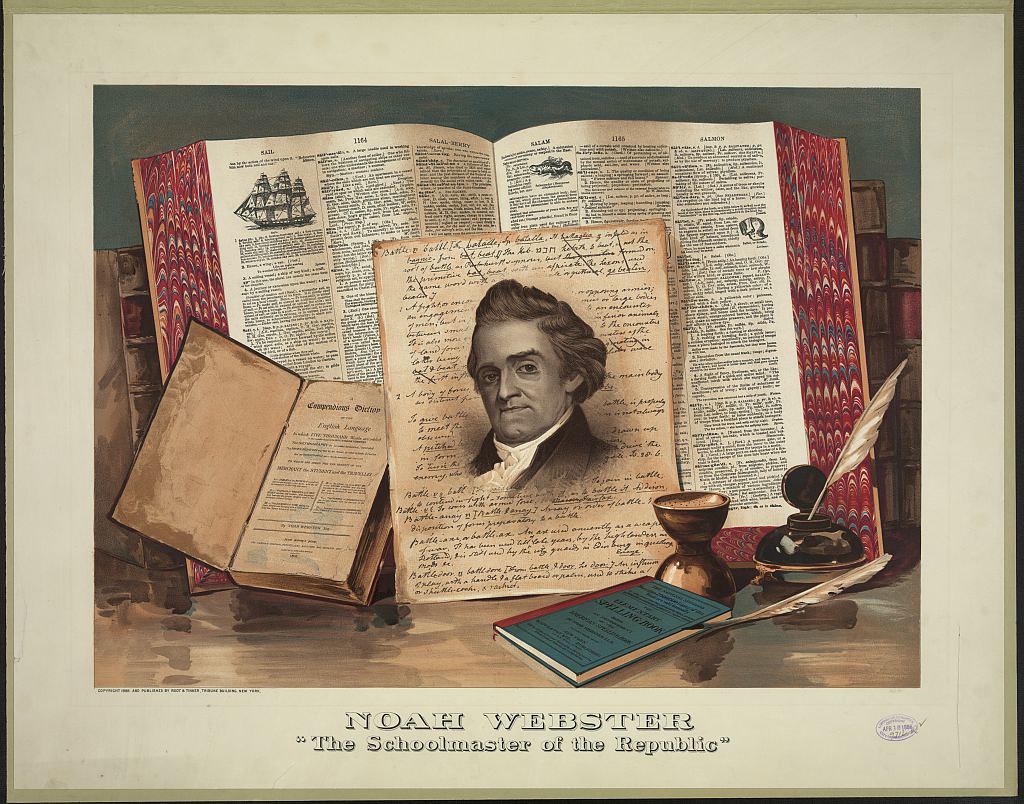

Webster’s Dictionary

Noah Webster (1758-1843) published the earliest American dictionary, which championed American meanings and spellings over British ones. Since then, language differences have continued to evolve, giving added credence to George Bernard Shaw’s observation that Britain and America were two countries divided by a common language.

Creative New Names

In Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that where European aristocracies preferred precision and stability in language, democratic America yearned for exuberance and innovation.

In the early 19th century, new words began to appear to give an air of respectability to some undesirable jobs. Grave-digger became undertaker, and later, a series of related terms came into being: funeral director, mortician, mortuary science, memorial park. Elegant words displaced less pleasant-sounding ones: cockerel became rooster; comfort station replaced toilet, and limb substituted for leg.

With the building out of America’s towns and cities came the need for new words to describe buildings, infrastructure, and industry: lot, waterfront, subdivision; log cabin, adobe, apartment, tenement, shanty; project, condominium, row house, backyard, clapboard, siding, baseboard; back road, freeway, parkway, sidewalk, railroad; boxcar, caboose; canned goods, gasoline, sidetrack, make the grade.

Pronunciation

American English retains a particular characteristic of 17th-century English that British English has largely lost—the pronunciation of “r” after a vowel. Most of the US is “rhotic”, meaning that “r” is pronounced in words such as hard and weather. British English is largely non-rhotic, so hard sounds more like “hahd”. Ireland, Scotland and the West Country (Devon, Cornwall) have retained rhotic pronunciation, so the waves of immigrants from these areas only bolstered rhoticity in the US.

Other differences include pronouncing consonants that are silent in British English, for example, schedule, which sounds like “shedule” in Britain.

Differing Conventions

Some conventions differ in American English compared to British, with American usually being simpler: flavor replaced flavour; aluminum instead of aluminium; catalog for catalogue. American English also simplified the francophile words of Victorian England: check instead of cheque; program replaced programme.

A number of words in American English come from business, sports, and entertainment: bottom-line, breakeven, merger, downsize; ballpark, gameplan, cheapshot, pass the buck; disc jockey, movies.

There are more examples than you can shake a stick at!

Two Countries Divided by a Common Language?

Well, we’re divided by a “big pond” for sure. Transatlantic crossings in the 17th and 18th centuries were hazardous and long—taking six weeks or more. So for some 200 years prior to the advent of steamships, communication between Britain and America was severely challenged. That’s a long time for language to change, adapt, and evolve.

Today, we celebrate the nuances that separate our versions of the English language—the differences are fun and entertaining.

Sources

Wikipedia.org

Library of Congress.

Speaking American: A History of English in the United States by Richard W. Bailey.