Do you like human history? How about art and culture? Variety? London?

If you answered yes to any of the above, then we can heartily recommend the British Museum as a place you will find hours of pleasure.

Don’t have time to visit? Too far away?

Fret not, dear reader, because we are going on a virtual tour without leaving our seats.

By clicking on the “Google Street View” links at the end of each section, we can go inside the British Museum and get a good look at these exhibits as though we were actually there. Amazing!

10 of the best things to see at the British Museum (from your favorite armchair).

1. The Sutton Hoo Treasures

Sutton Hoo is a fascinating archaeological site located near Woodbridge, Suffolk

The burial is believed to be of a high-ranking figure, possibly even a king, from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles—a tribe originating from Angeln in Germany—now an area called East Anglia (shown in re. The artifacts provide valuable insights into their beliefs, customs, and social structure.

The cemeteries were in use at a time when Rædwald, the ruler of the East Angles, held sway among the English people and played an important role in establishing Christian rule in England. It was a time when myths and legends melded with the historical record.

The site has been vital in understanding the early Anglo-Saxon period.

2. The Rosetta Stone

To appreciate the significance of the Rosetta Stone, we need to understand how difficult it was to decipher Egyptian hieroglyphs without it. For about 1400 years, from the time hieroglyphs ceased to be used until the 1820s, they were a complete mystery.

The key to the mystery lay in three versions of the same text that are inscribed on the stone’s surface. The upper text is Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, the middle portion Demotic script, and the lowest is Ancient Greek.

By transcribing between the alphabets, French scholar Jean-François Champollion was able to unlock the secrets of the Ancient Egyptians.

The story of the Rosetta Stone’s discovery is almost as interesting as the stone itself. In 1799, one of Napoleon’s soldiers found it while on the Napoleonic expedition to Egypt. But just two years later, British forces defeated the French in Egypt and took the stone back to England. It is now the most-visited object in the museum.

3. The Hinton St Mary Mosaic

Thought to be one of the oldest known representations of Jesus Christ, the Hinton St Mary Mosaic is a large Roman mosaic named after the village where it was discovered in Dorset, England.

Christ is portrayed as clean-shaven with the letters chi (X) and rho (P) behind his head—the first two letters of the Greek word for Christ “Christos”.

Britain was a far-flung province of the Roman Empire at the time Emperor Constantine converted to Christianity in AD 312. The mosaic was found in the dining room or house-church of a villa belonging to a Roman aristocrat.

4. The Parthenon Sculptures

Originally part of the temple of Parthenon in the Acropolis of Athens, Greece, the marble sculptures were brought to Britain by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin in 1816 under a controversial royal decree from the Ottoman Empire that had ruled Greece since 1460.

While some supported the move, cultural leading figure and poet Lord Byron disapproved, likening the removal of the sculptures to vandalism or looting.

In 2014, the Greek government urged Britain to return the sculptures as part of its efforts to restore one of the world’s greatest cultural monuments. But Professor of Law and Art at Stanford University, John Merryman argued that the sculptures were obtained legally, adding that the Ottoman sultan had no interest in the Parthenon and permission to remove the sculptures was also a token of gratitude to the British for checking Napoleon’s expansion in the region.

5. The Bust of Ramesses (The Younger Memnon)

Ramesses II, renowned as Ramesses the Great, stands as an iconic figure in ancient Egyptian history, often hailed as the most formidable pharaoh of the Egyptian Empire.

Ascending to the throne during his youth, Ramesses orchestrated triumphant military expeditions that reinstated Egyptian dominance in Canaan, encompassing present-day Israel and Lebanon. His rule endured an astonishing span, reaching the remarkable age of approximately 91 years.

Picture the grandeur of his army, a formidable force of 100,000 soldiers, their chariots gleaming under the scorching Egyptian sun. Ramesses’ vision extended beyond military conquests; he embarked on ambitious construction projects of monumental proportions, mobilizing the populace to reshape the landscape of Egypt.

His unwavering commitment to leaving an indelible legacy ensured that his colossal structures and accomplishments would transcend time, solidifying his status as a pharaoh of unparalleled significance in the annals of Egyptian civilization.

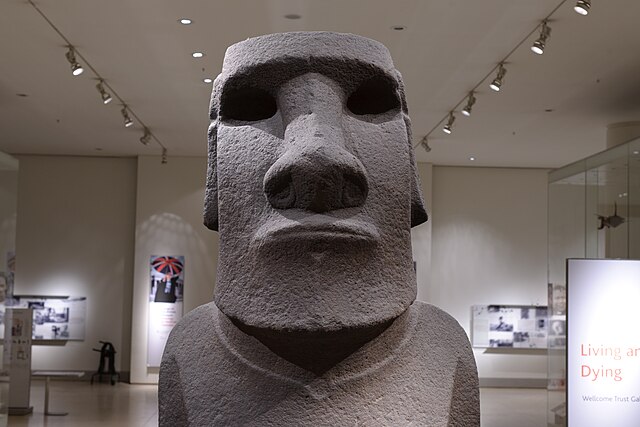

6. Easter Island statue

The Easter Island statue at the British Museum has been described as “the finest example of Easter Island sculpture”.

At the time it was removed, it was identified by islanders as being of Hoa Hakananai’a, meaning “stolen or hidden friend” in Polynesian.

Made from a block of flow lava, Hoa Hakananai’a’s blocky face with prominent nose and heavy brow watched over an extinct volcano, with his back to the sea.

Found in 1868 by the Royal Navy, the statue was offered as a gift to Queen Victoria, who proposed it should be given to the British Museum.

7. Samurai Armor

From a country that was never invaded came the lightest, strongest, and most lethal weapon in the world—the samurai sword.

An equal, if not greater, level of sophistication and precision was required to protect samurai against such a cutting weapon. In addition to swordsmanship, samurai practiced archery on horseback and needed very lightweight armour that allowed for freedom of movement.

Samurai armour was made from leather and iron scales, connected together with leather and silk lace. Specific patterns and colors of silk thread would identify noble families, but could take many months to complete just one suit of armour.

Even as the 16th century introduced firearms from Portugal, Japanese armour makers were able to make bullet-proof armour using a combination of iron and steel plates.

8. Jade terrapin from India’s Mughal court

Carved from a single piece of jade and weighing 90 lbs (41kg), the Jade Terrapin from Allahabad dates from the early 17th century Mughal Empire.

Covering vast areas of the Indian subcontinent and Afghanistan, the Mughal Empire was best known for Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor, who constructed the Taj Mahal at Agra as well as several other monuments.

Shah Jahan’s predecessor was Jahangir, who had the jade terrapin carved as a decorative ornament for the landscaped pools of his palace gardens at Allahabad.

Discovered by accident in 1803 during engineering work, it’s historical value was immediately recognized and it was shipped to England and later bequeathed to the British Museum in 1830.

9. Cartonnage mummy cases

Cartonnage, a crucial material in the realm of ancient Egyptian funerary practices, served as the foundation for intricately adorned masks and mummy cases. Crafted from layers of papyrus encased in plaster, the technique resembled the art of papier-mâché. Once dried, cartonnage could be skillfully molded into a shell resembling the human form, providing a canvas for elaborate paintings and gilded embellishments.

In Ancient Egypt, meticulous care of the deceased was imperative, driven by the belief in appeasing Osiris and ensuring a prosperous afterlife. Over four millennia, the mummification process underwent minimal evolution. Removal of perishable organs and desiccation of the corpse were standard procedures. The brain, liquefied and drained through the nose, showcased the meticulous nature of the process. Filling the abdominal cavity with aromatic herbs, dehydrating with salt, and wrapping the body in bandages soaked in waterproof and antimicrobial gum culminated in the preservation of the deceased.

The British Museum houses a significant collection of 120 mummies, offering a profound glimpse into the ancient Egyptian rituals surrounding death and the afterlife.

10. The Mechanical Galleon

The Mechanical Galleon is a clockwork automated table ornament in the shape of a ship.

Made by Hans Schlottheim (1545–1625), a goldsmith and clockmaker from Augsberg Germany, the mechanical galleon had moving figures and played music. Seven figures were made to walk before the seated Holy Roman Emperor as trumpets blared, and the cannons could even produce smoke.

Clockwork was a novelty in the 16th century and the Mechanical Galleon might have entertained guests at imperial banquets—its three clockwork mechanisms driving its movement across a table, guns blazing and trumpets blowing.

References

British Museum

Wikipedia

Ancient Lives, New Discoveries—The Telegraph