Once an important working market and the backdrop for the musical My Fair Lady, Covent Garden today is one of London’s biggest tourist magnets, attracting over 44 million visitors annually.

Here are 10 fascinating facts about this historic area of London.

1. Covent Garden was once the bustling center of an Anglo-Saxon trading town

“A trading centre for many nations who visit it by land and sea”

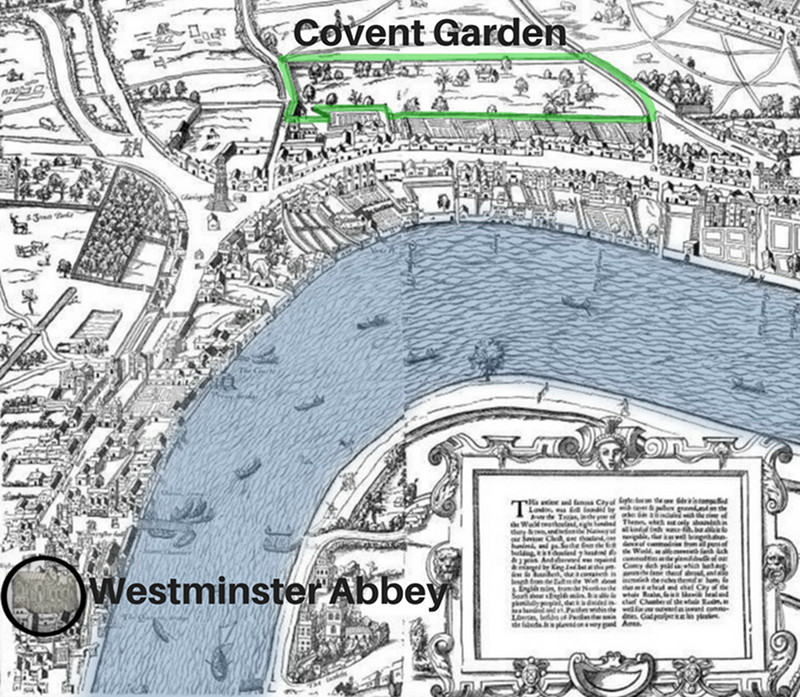

Established about a mile to the west of Londinium—the old Roman settlement now known as the City of London or “the Square Mile”—was a 7th-century Anglo-Saxon trading town called Lundenwic, centered around the area that is now Covent Garden.

Described by the English monk, Bede the Venerable, in the 8th century as “a trading centre for many nations who visit it by land and sea”, the Old English term -wic derived from the Latin word vicus for “trading town”—so Lundenwic meant “London trading town”.

During Viking invasions in the 9th century, the Danish “Great Heathen Army” sacked Londinium and held it until 886 when Alfred the Great, “King of the Anglo-Saxons”, recaptured it and repaired the Roman walls.

As trading shifted to Londinium once more, Lundenwic was abandoned and became a wasteland.

Lundenwic became known as Ealdwic, meaning “old trading town”.

Recent excavations in Covent Garden have revealed that the early Anglo-Saxon settlement once stretched from where the National Gallery is now to the area called Aldwych—some 150 acres.

2. Covent Garden derives its name from the French word couvent meaning Convent

“Covent Garden” is essentially a corruption of “Convent Garden” using the French couvent derivation as opposed to the Latin conventus.

Couvent means a religious building such as a nunnery or monastery.

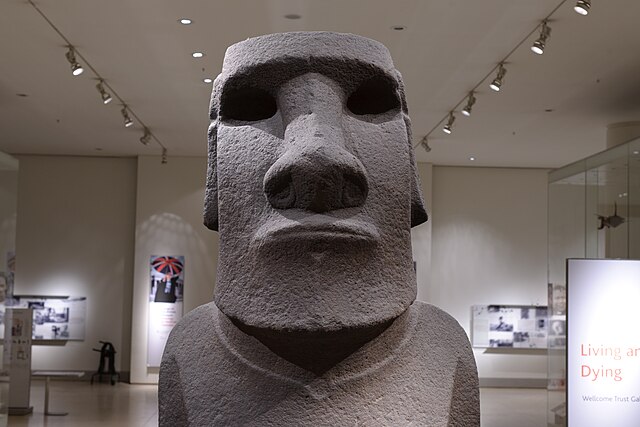

By the 13th century, most of the present Covent Garden area was land belonging to Westminster Abbey which included a walled vegetable garden tended by the monks.

3. Henry VIII seized the lands of Covent Garden and gave them to a friend

Dissolving the monasteries in the 16th century gave King Henry VIII plenty of new lands, including those formerly owned by Westminster Abbey.

Covent Garden was given to John Russell, 1st Earl of Bedford.

Sitting idly by for over 100 years in the family estate, it wasn’t until Francis Russell, 4th Earl of Bedford had the bright idea to build a house on the land, that the Covent Garden we know today got its start.

Two of the area’s street names—Russell Street and Bedford Street—commemorate the family’s involvement in Covent Garden’s beginnings.

4. Covent Garden was designed by Royal Architect Inigo Jones

Commissioning Inigo Jones to build a square “fit for Gentlemen with ability”, the Earl of Bedford also asked Jones to build a church—St Paul’s—for his aristocratic clientele.

“fit for Gentlemen with ability”

Inigo Jones is considered to have been the first significant architect of the early modern period.

To keep costs down for the church, the Earl requested nothing more extravagant than a barn.

“You shall have the finest barn in London”, replied Jones.

The porticoed St Paul’s Church has sat proudly overlooking the piazza to this day.

5. Covent Garden was the first piazza in London

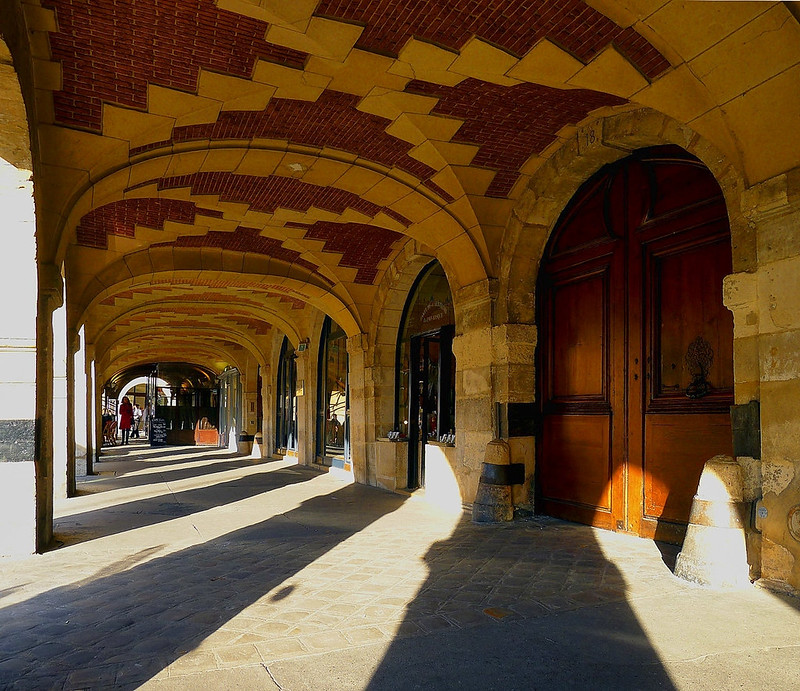

“A passageway reminiscent of the Place des Vosges”

Influenced by the grand piazza’s of Europe, Covent Garden’s piazza was originally bounded by “portico houses” on its north and east sides with continuous arcades running underneath, creating a passageway reminiscent of the Place des Vosges in Paris.

Known as the Great Piazza and the Little Piazza respectively, the houses sold quickly to aristocrats and court society.

Influencing the overall design of Covent Garden was Inigo Jones’s knowledge of town planning in Europe, particularly the Grand Piazza in Livorno, Tuscany.

6. Covent Garden has run a market since 1656

Setting up stalls against the garden wall of Bedford House, the early market traders served mostly wealthy tenants.

Wooden rails were erected around the piazza and traders with baskets, trestles and carts congregated on the south side outside the rails.

After the Great Fire of London in 1666, scores of Londoners left the City and descended on Covent Garden.

Dozens of traders hawking fruit and vegetables became an established feature of Covent Garden.

Granted a Royal Charter in 1670, the Earl of Bedford sought to regulate the market’s spread.

And in 1830, his descendant John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, commissioned English architect Charles Fowler to build a neo-classical market building that remains at the heart of Covent Garden today.

7. Covent Garden was an 18th-century red-light district

“Described the physical appearance of the Covent Garden Ladies and their sexual specialties”

Published from 1757 to 1795, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies was an annual directory of prostitutes working in and around Covent Garden.

In lurid detail, the pocketbook described the physical appearance of the Covent Garden Ladies and their sexual specialties.

Miss B of Old Compton is described as:

Miss R from Rathbone Place:

Kitty Fisher and Fanny Murray were two high-class courtesans.

Connections in high places had their advantages.

Famed prostitute Betsy Cox was refused entry to a gathering of polite society at the newly opened Pantheon assembly rooms.

But the Duke of Fife came to her aid, drawing his sword to enforce her entry.

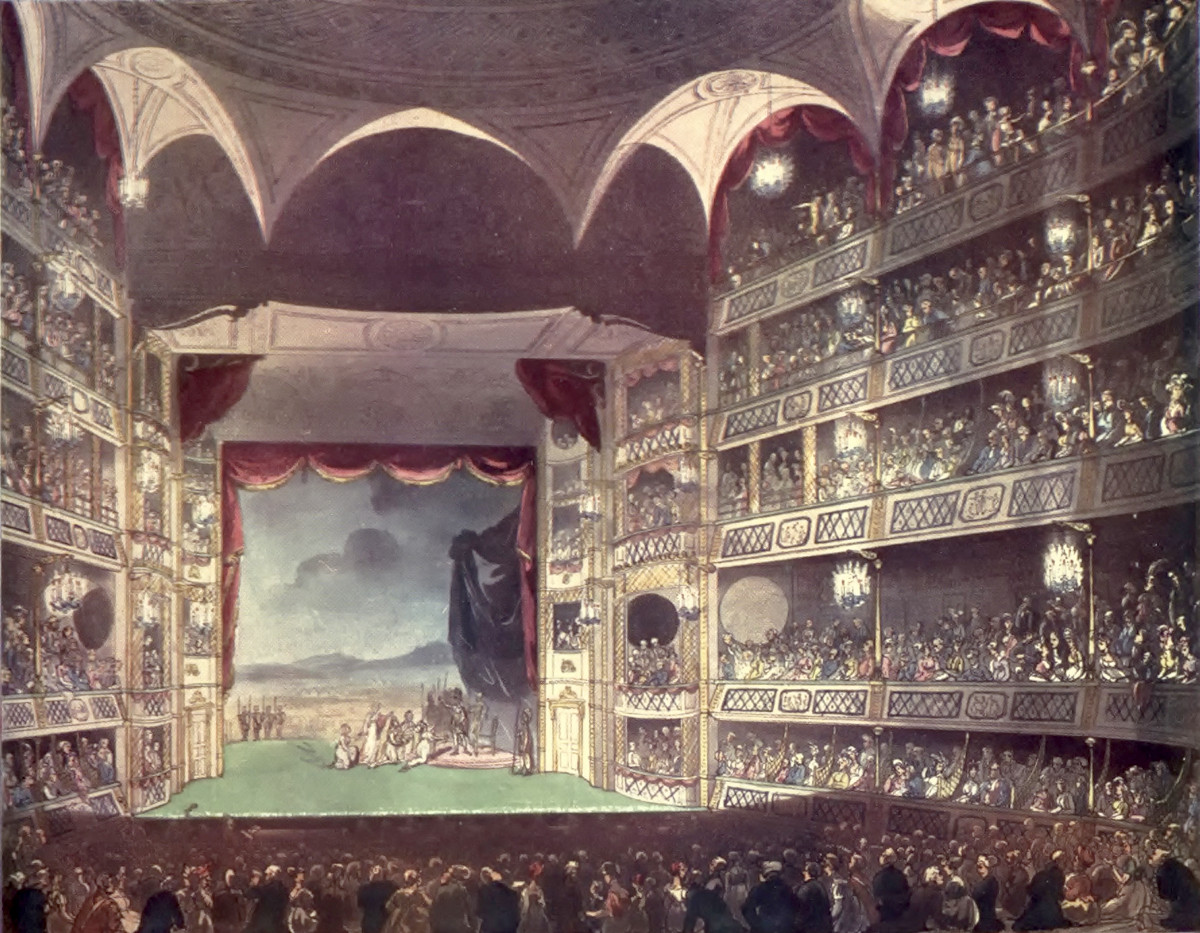

8. Both the Royal Opera House and the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane are said to be haunted

During construction work in 1999, workers were struck by flying debris.

Bits of brick and metal would be flung at them throughout the day.

Could the work have awoken the resident poltergeist?

Since security was so tight, it was thought almost impossible to be someone who walked in from the street.

Could the work have awoken the resident poltergeist?

Paranormal expert Tom Ogden calls the Theatre Royal one of the world’s most haunted theatres.

Frequenting the theatre, the appearance of any one of its ghosts is said to signal good luck for the actors or production.

A famous ghost called the “Man in Grey” haunts the theatre

According to legend, a famous ghost called the “Man in Grey” was an 18th-century nobleman who was stabbed to death in the theatre, his skeletal remains having been found in a walled-up passage in 1848.

He wears a cape, a tricorne hat, riding boots, and a sword and is often seen in the upper circle moving along the rear gangway near the royal box where the remains were discovered.

Could the spirits of patrons past still visit the theatre?

Or could it be Mr Bean who just got lost on his way to the restrooms?

9. Covent Garden has over 60 pubs and bars

The area’s oldest pub earned the nickname ‘Bucket of Blood'”

There’s no shortage of liquid refreshment to accompany the cultural entertainments in Covent Garden.

Listed as historically important buildings, several pubs will transport you back in time.

With a reputation as the oldest pub in the area, the Lamb and Flag will take you back to a time of bare-knuckle prize fights in the early 19th century.

So gruesome were these gladiatorial clashes that the pub earned the nickname “Bucket of Blood”.

The Freemasons Arms on Long Acre is linked with the founding of the Football Association in 1896.

Charles Darwin attended the annual meeting of the Philoperisteron Society for pigeon fanciers here on 8 January 1856 and became a member later that year.

10. Covent Garden street performers run shows every day of the year except Christmas Day

Street performances have long been a tradition at Covent Garden.

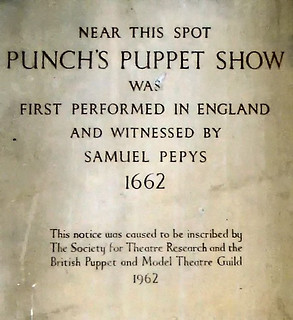

17th-century diarist Samuel Pepys recorded the first mention of a Punch and Judy show in Britain.

Licensed for street entertainment, performers audition for timetabled slots in a number of venues around Covent Garden, including the North Hall, West Piazza, and South Hall Courtyard.