Can you imagine going to school here?

That’s a reality for 770 lucky children aged between 13 and 18.

Once a country home of the landed gentry, Stowe House is now a private school in the beautiful Buckinghamshire countryside.

It may not teach witchcraft and wizardry like Hogwarts, but it certainly is a magical place nonetheless.

A New Vision for Education

Founded in 1923, Stowe School’s first Headmaster J.F. Roxburgh said that Stowe focused on the individual, instilling an ethos of liberal learning enthused with beautiful surroundings so that every pupil would know beauty when they saw it throughout their whole lives.

Roxburgh wanted pupils and staff to relate in a civilized and open way, addressing each pupil by their first name, and instilling confidence and respect based on Christian values.

Did it work?

Well, consider that by 1939, nearly 60% of pupils went on to Oxford or Cambridge Universities—higher than any other private school in Britain.

And what did Stowe’s schooling methods do for pupils’ career prospects you may wonder.

Known as Old Stoics, former pupils of Stowe include: multi-billionaire Sir Richard Branson, founder of the Virgin Group; Baron John Sainsbury, the President of J Sainsbury’s, Britain’s second largest supermarket; Dalton Philips, CEO of Morrisons, the fourth largest supermarket in Britain; Baron Alistair McAlpine, treasurer for Margaret Thatcher’s government, founder of his own publishing company, and director of the McAlpine construction business at age 21; David Niven, actor and novelist who won an Academy Award for Best Actor; and Baron Michael Grade, TV executive for the BBC and ITV, and life peer in the House of Lords.

The Greatest Debtor in the world

Originally owned by Sir George Gifford, Knight and Member of Parliament, Stowe House was later leased to English politician Sir Peter Temple who also served as High Sheriff of Buckingham (1592 – 1653).

Sir Peter’s son, John Temple, bought Stowe House in 1589 and it stayed in the Temple family until it was acquired by the governors of Stowe school in 1922.

The Temple family name became somewhat extended to Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville by a succession of marriages to wealthy heiresses.

And not all Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenvilles were good at managing their finances.

Born with a silver spoon in his mouth, Richard Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenville, 2nd Duke of Buckingham and Chandos managed to rack up debts of almost £1.5m—equivalent to about $170m today.

Called the “Greatest Debtor in the world”, the dashing rogue—imagine Jane Austen’s Mr Wickham having Mr Darcy’s fortune and squandering it all—had to flee the country in 1847 to escape his creditors, who were forced to sell the family silver, literally and figuratively.

Besides the family’s London home of Buckingham House on Pall Mall, the family estates in Ireland, Hampshire, Gloucestershire, Somerset, Cornwall, Oxfordshire, and Northamptonshire were sold.

How many estates does one family need you may wonder?

Then there were paintings and other works of art, 21,000 bottles of wine, and 500 bottles of hard liquor.

Reduced to the bare bones of “just” 10,000 acres, the estate of Stowe House even had to cut gardening staff from 40 to 4.

This was austerity on steroids, and yet the Temple-Nugent-Brydges-Chandos-Grenvilles were still wealthier than most people are today.

The Medici Lions

Dating from the late 1700s, the Medici lions stand proudly guarding the main entrance of Stowe House.

Commissioned by Ferdinando I de’Medici, they were originally created for the Villa Medici in Rome and purchased by Richard Temple for Stowe House.

Sculpted by John Cheere, an English sculptor specializing in lead statues for gardens, they were originally painted a golden yellow to match the limestone of Stowe’s buildings.

Stowe has one of the largest concentrations of grade I listed buildings in England.

Here are some examples of these beautiful buildings and structures that adorn Stowe Gardens.

Placed on the Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest, there are three types of listed status in England and Wales:

Grade I: buildings of exceptional interest.

Grade II*: particularly important buildings of more than special interest.

Grade II: buildings that are of special interest, warranting every effort to preserve them

The Palladian Bridge

Designed to mimic the bridge at Wilton House in Wiltshire, the Palladian Bridge at Stowe is lower, with shallow ramps to allow horse-drawn carriages to cross as they ferried visitors on a tour of the grounds.

Flanked by pedimented pavilions with attached columns framing semi-circular arches, three of the five supporting arches have carved keystones.

The Temple of British Worthies

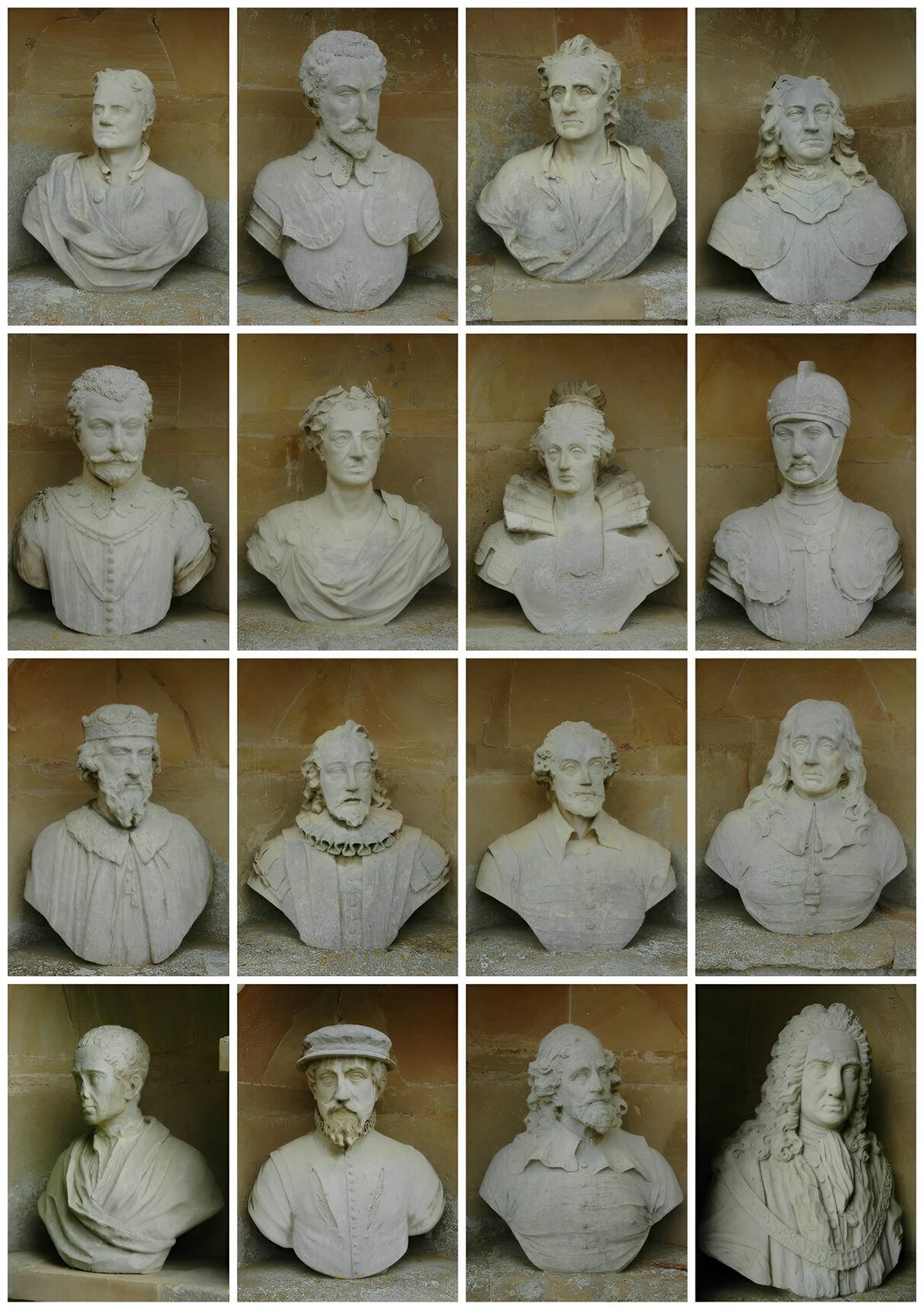

Built to honour eight of the greatest Britons known for their actions and deeds, and eight for their thoughts and ideas, this curving stone wall has six busts either side of a central pier.

Two further busts are at either end and two more on the rear.

Influenced by the Whig politics of the Temple family, the 16 “British Worthies” are:

Sir Isaac Newton—English mathematician, astronomer, and physicist widely recognised as one of the most influential scientists of all time and a key figure in the scientific revolution.

Sir Walter Raleigh—English landed gentleman, writer, poet, soldier, politician, courtier, spy and explorer, known for popularising tobacco in England.

John Locke— English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the “Father of Liberalism”.

John Hampden—English politician who was one of the leading parliamentarians involved in challenging the authority of Charles I of England in the run-up to the English Civil War. He became a national figure when he stood trial in 1637 for his refusal to be taxed for ship money.

Sir Francis Drake—English sea captain, privateer, navigator, slaver, and politician of the Elizabethan era. Drake carried out the second circumnavigation of the world in a single expedition.

King William III—widely known as William of Orange (a feudal state in Provence, in the south of modern-day France), he was chief magistrate of several Dutch provinces, and King of England, Ireland, and Scotland from 1689—1702.

Queen Elizabeth I—Queen of England and Ireland from 1558—1603. Daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, the Elizabethan era was a period of flourishing English playwrights and seafaring adventurers.

The Black Prince—the eldest son of King Edward III and Philippa of Hainault, and the father of King Richard II of England. His exceptional military leadership and victories over the French at the Battles of Crécy and Poitiers made him very popular in England during his lifetime.

King Alfred—King of Wessex, the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in the south of Great Britain, from 871 to 899.

Sir Francis Bacon—English philosopher, statesman, scientist, jurist, orator, and author. Called the father of empiricism, his works argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature.

William Shakespeare—English poet, playwright, and actor, widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world’s pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England’s national poet, and the “Bard of Avon”.

John Milton—English poet, polemicist, man of letters, and civil servant for the Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell. Best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost, he wrote at a time of religious flux and political upheaval.

Alexander Pope—English poet best known for his satirical verse, his translation of Homer, and his use of the heroic couplet—a traditional form for English poetry.

Sir Thomas Gresham—English merchant and financier who founded the Royal Exchange in the City of London and acted on behalf of King Edward VI and queens Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Inigo Jones—English architect and first to employ Vitruvian rules of proportion and symmetry in his buildings, prompting the rebirth of Classical architecture during the Renaissance.

Sir John Barnard— British Whig politician and Lord Mayor of London. Whig politics was central to the beliefs of the Temple family, with its origin lying in opposition to absolute monarchy and support for the constitutional monarchy we still enjoy today.

The Rotondo

Designed by the English architect Sir John Vanbrugh (best known for his work on Blenheim Palace and Castle Howard), the circular temple of ten unfluted Roman columns is raised on a podium of three steps.

Standing at its centre on a tall decorated plinth is a gilt statue of Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty, desire, sex, fertility, prosperity and victory.

Landscaped Gardens

Stowe is said to be the first English garden for which a guidebook was written.

Evolving from an English Baroque garden influenced by Versailles into a landscaped park blending with the natural contours of the terrain and allowing nature to dominate manmade structures.

Stowe Gardens were the largest and most elaborate example of an “English Garden” in Europe.

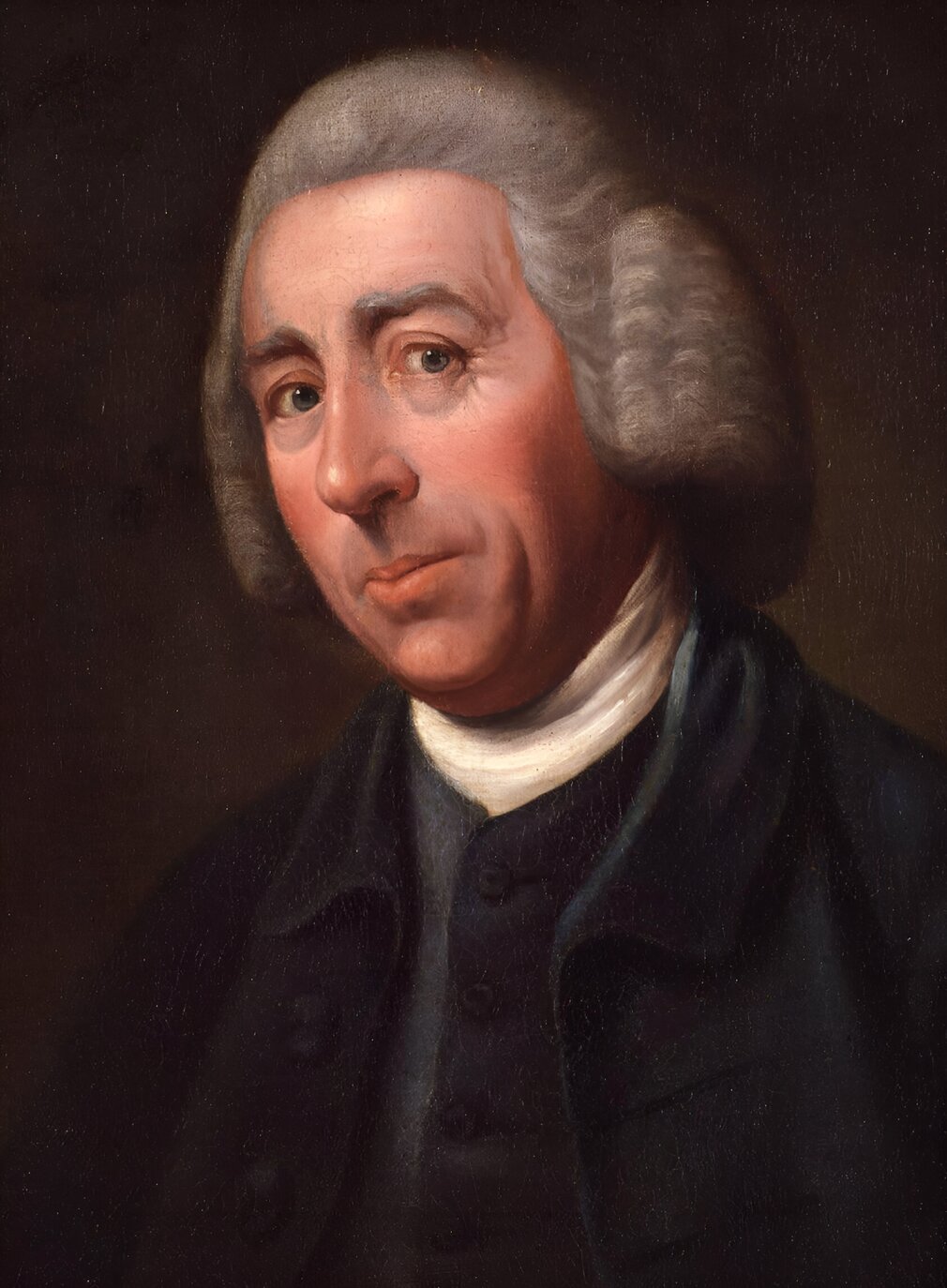

Among the outstanding designers and architects who worked on the gardens during the 18th century was Lancelot Brown, remembered as “England’s greatest gardener” and more commonly known as Capability Brown because he would say to clients that their gardens had “capability” for improvement.

Despite celebrating British imperial conquest and artistic achievement, the 18th-century designers of Stowe Gardens sent future generations a cautionary warning.

That although the great nation of Britain liked to emulate the ancients, it was important to remain humble, and to remind ourselves that all manmade monuments eventually succumb to the mighty forces of nature.