The Largest Gothic Cathedral in Britain

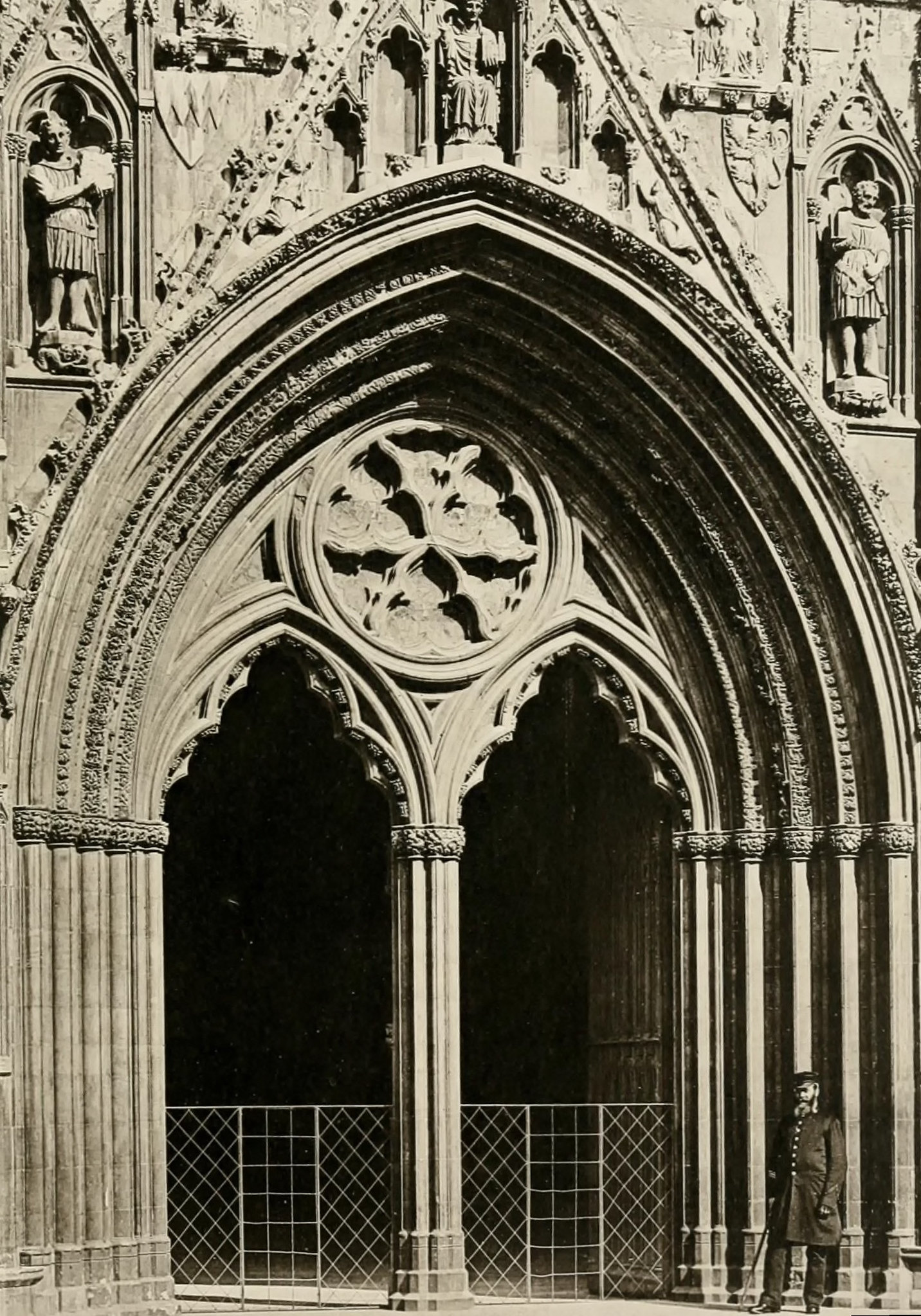

In 1215, Archbishop of York, Walter de Gray ordered the construction of a Gothic structure for the north of England to rival Canterbury Cathedral in the south.

Gothic style was about soaring to the sky, and therefore Heaven, with pointed arches, lots of light and ornamentation.

Instead of starting from scratch, the new Gothic form was built on and around the existing Norman Minster dating from 1080—the foundations of which can be seen today.

Declared complete and consecrated in 1472, York Minster has survived wars, plague, political upheaval, structural crisis, and local rebellion … and lived to tell the tale.

To this day, the most significant building rising above York is the 800-year-old medieval Minster.

The term “minster” is given to churches established in the Anglo-Saxon period as missionary teaching churches. Today, it’s used as an honorific title.

Developed during the Gothic period (12th—16th c.), “flying buttresses” were arched structures used to support the walls of medieval cathedrals.

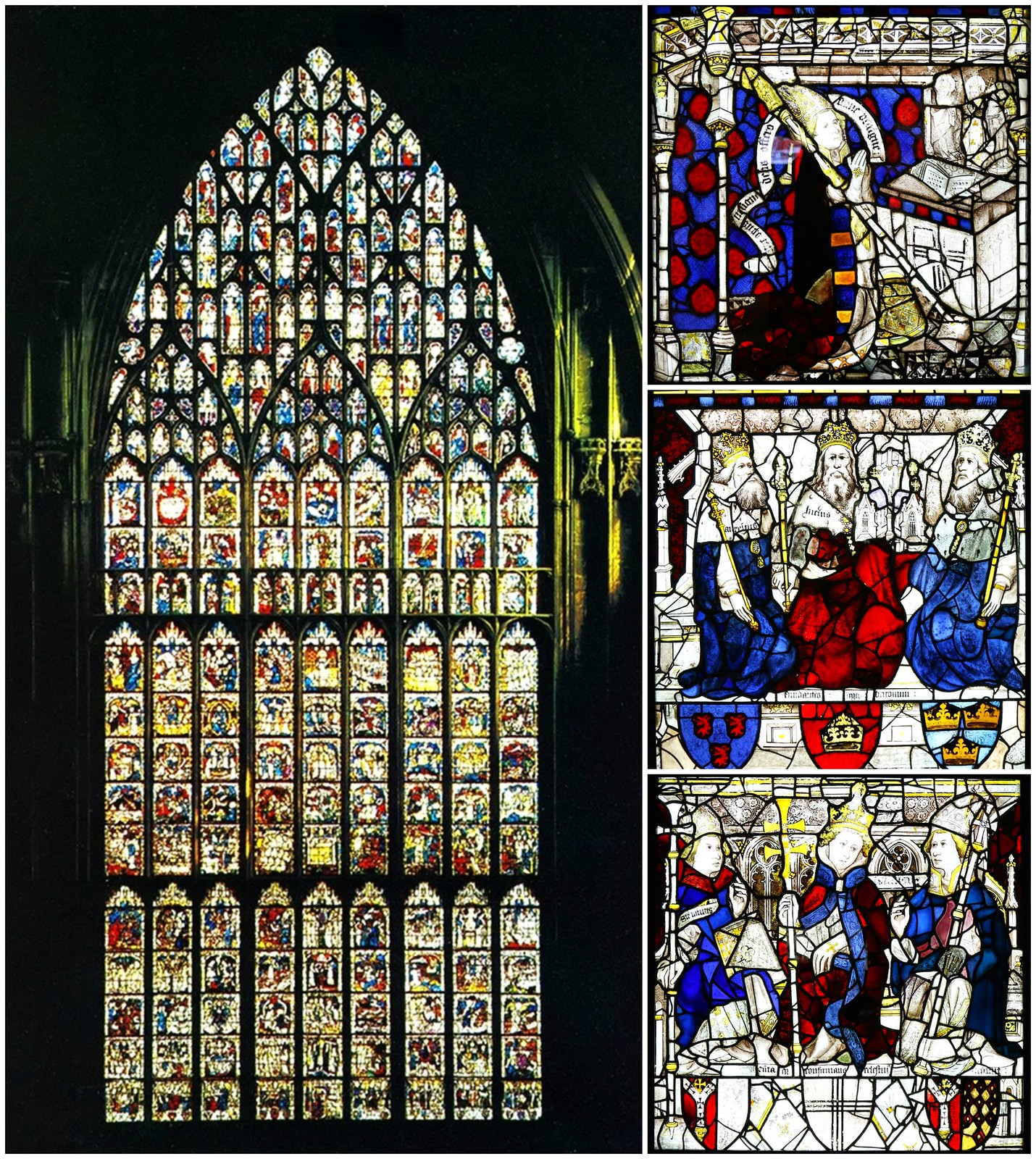

The Largest Expanse of Medieval Stained Glass in the World

When it comes to stained glass, York Minster is in a class of its own, with some of the finest examples of medieval stained glass in the world, dating as far back as the 12th century.

Completed in 1408, the Great East Window in the Lady Chapel is the largest expanse of medieval stained glass in the world.

The size of a tennis court, the Great East Window was created between 1405 and 1408 by master glazier John Thornton and shows intricately detailed scenes from the book of Genesis.

In the below detail, Saint John (bottom left) is instructed by an angel to write down what he saw in his vision and send it to the seven churches of Asia.

John Thornton’s clever design combines all seven churches into one image, each represented by an archbishop standing in a shrine-like building.

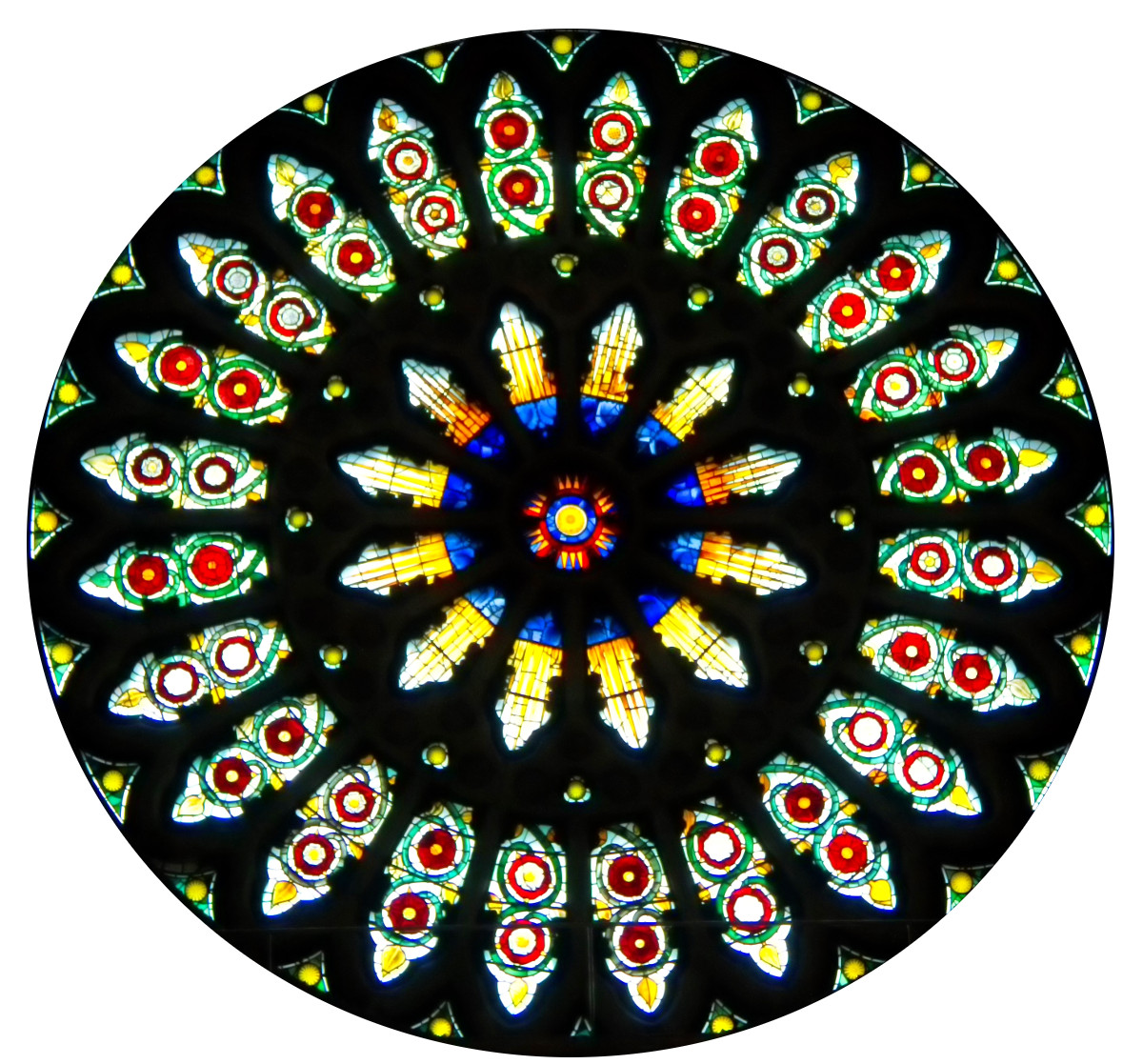

Commemorating the union of the royal houses of York and Lancaster following the Wars of the Roses, the Rose Window in the south transept dates from about 1500.

The Five Sisters Window in York Minster’s North Transept is the only memorial in the country to women of the British Empire who lost their lives during the First World War. Each lancet is over 52 feet (16 m) high.

Dating from the mid-1200s, the window was removed during the First World War to protect it during German Zeppelin raids.

The Great West Window contains a heart-shaped design colloquially known as ‘The Heart of Yorkshire’.

Built between 1338 and 1339, it shows the hierarchy of the Church as you look up the window.

At the base level are eight Archbishops of York, with their Apostles above, followed by panels showing the life of Christ and the Virgin—the Annunciation, Nativity, Resurrection, and Ascension. The top panels show Mary sitting beside Christ in Heaven.

The window is known as ‘the heart of Yorkshire’ due to the shape of its upper stonework.

The Widest Gothic Nave in England

York Minster’s nave is the widest Gothic nave in England and has a wooden roof (painted so as to appear like stone) and the aisles have vaulted stone roofs.

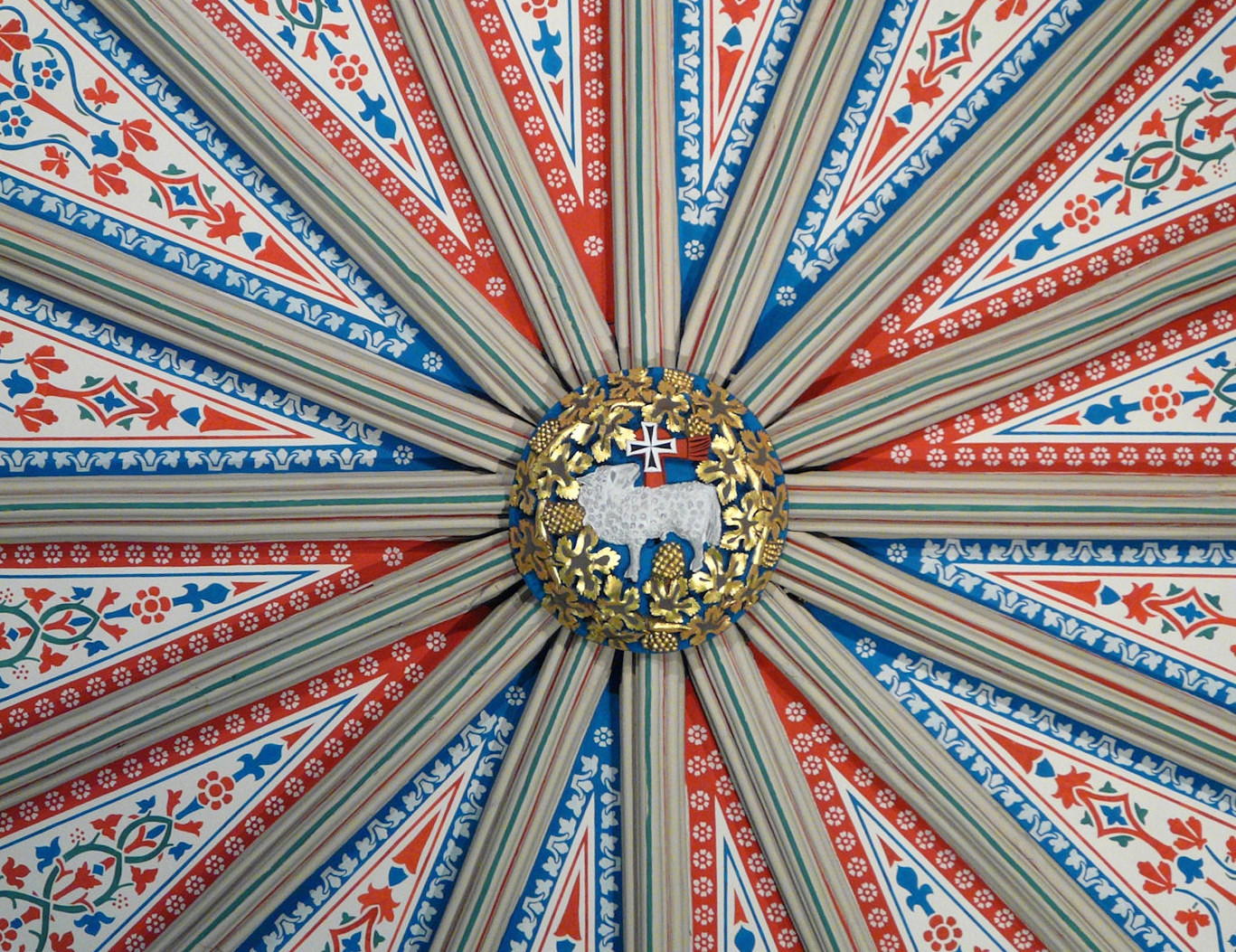

The Chapter House

Windows cover almost all of the upper wall space of the highly decorated Chapter House, filling it with light.

Innovative design and a light wooden roof meant that the buttressed walls could support the ceiling without the need for a central column, creating a beautiful open space.

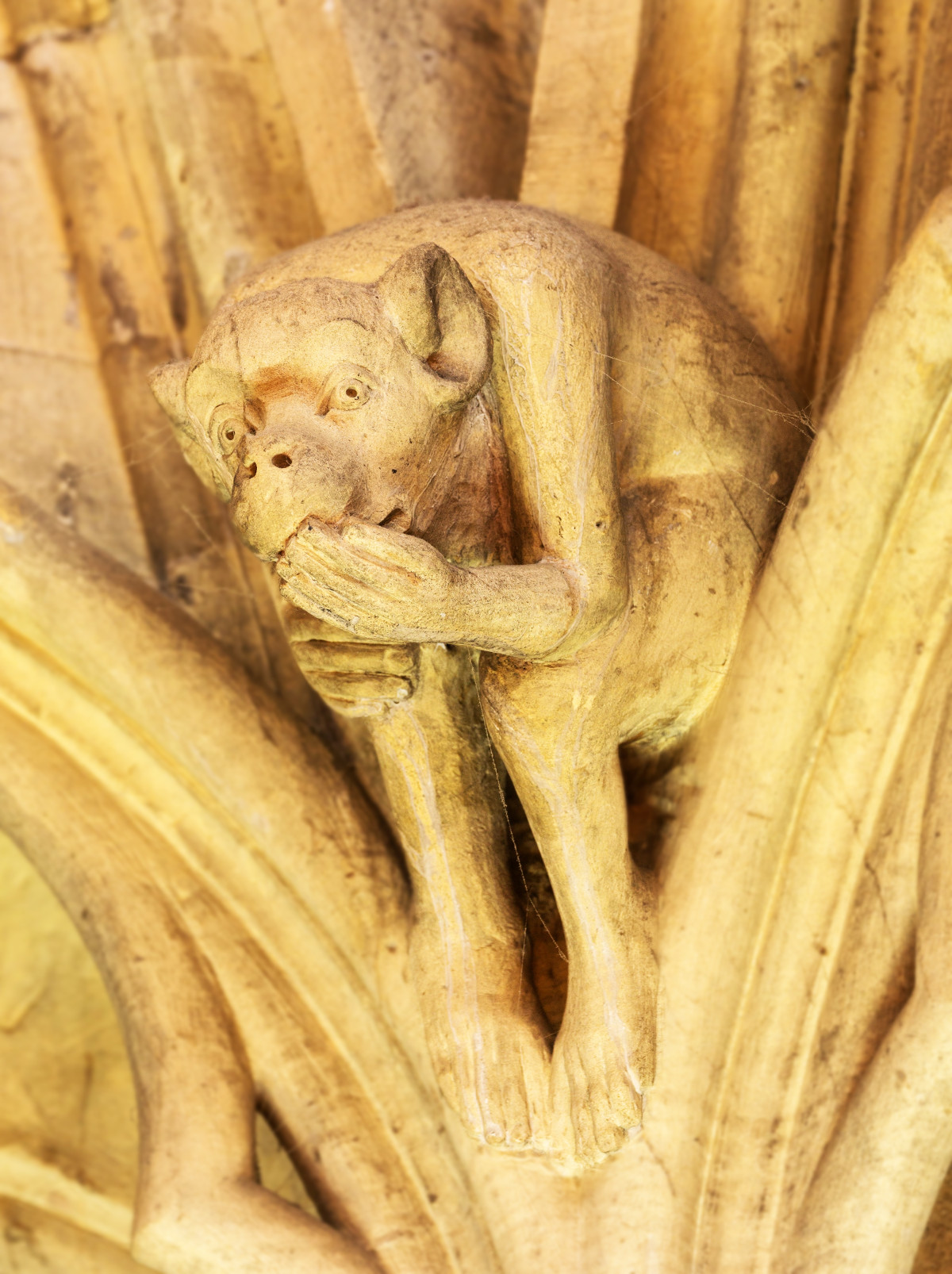

Grotesques

Grotesques are fantastical or mythical figures used for decorative purposes. Gargoyles are forms of grotesque that include a drainage spout to help prevent heavy rainwater running down the face of the building.

York Minster is covered with grotesques inside and out.

Current stonemasons working on the finishing touches of the York Minster restoration have carved sometimes amusing grotesques doing unusual things.

This chap will eventually be baring his derriere to all and sundry from a lofty position above the city, affixed to York Minster.

The 11-ton Great Peter Bell

The clock bells ring every quarter of an hour during the daytime and Great Peter strikes the hour.

Great Peter is the name of the northwest tower’s bell, weighing in at almost 11 tons. The six other bells that ring every quarter of an hour weigh 3 tons each.

Before Evensong each evening, hymn tunes are played on a baton keyboard connected with the bells, but occasionally anything from Beethoven to the Beatles may be heard.

Reformation and Restoration

The English Reformation led to the looting of much of the cathedral’s treasures and the loss of much of the church lands.

Queen Elizabeth I was determined to have all traces of Roman Catholicism removed from the cathedral. Tombs, windows, and altars were destroyed.

During the English Civil War the city was besieged and fell to Oliver Cromwell’s forces in 1644, but York Minster was spared damage thanks to the influence of parliamentary general Thomas Fairfax.

In the 1850s services were suspended as the cathedral slumped deeply into debt.

To date, tens of millions of pounds have been spent on restoration work, but the results speak for themselves. York Minster will continue to reach to the skies for millennia to come.