Invaded, embattled, and besieged through centuries of warfare, Warwick Castle (pronounced “Worrick”) survived the ravages of history to become one of Britain’s major attractions and top 10 favorite castles.

It was King Alfred the Great’s daughter, Æthelflæd, who established the site of Warwick Castle in 914.

Built to defend the Kingdom of Mercia against invading Danes, the fortified settlement dominated the old Roman road called the Fosse Way, running southwest to northeast across the Midlands.

Following the Norman Conquest in 1066, King William I strengthened the fortification with a motte-and-bailey castle to maintain control of the Midlands while he marched northward.

Son of a powerful Norman family, Henry de Beaumont was appointed constable in 1088, to keep and maintain Warwick Castle for the king’s armaments.

Becoming the first Earl of Warwick two years later, Warwick Castle was passed through six generations of de Beaumonts, during which time it was rebuilt in stone in the 12th century.

As the first heiress of Warwick Castle, Margaret de Newberg, 7th Countess of Warwick took over the estate in 1242.

Margaret’s nephew, William Maudit, succeeded as the 8th Earl of Warwick.

Destroying the castle walls during a surprise attack in 1264 during the Second Barons’ War, Maudit’s wife, the Countess, was taken prisoner and only released on payment of a significant ransom.

Future owners would include seven successions of the de Beauchamp family, a Neville by marriage, two Plantagenets, three Dudleys, and no less than 15 Grevilles, the last of which sold Warwick Castle to the Tussauds Group, famous for Madame Tussaud’s wax museum in London.

Eleven of the owners were under 20 when they inherited, including a girl aged two and a boy aged three.

At least three owners died in battle, two were executed and one murdered.

Warwick Castle became Crown Property twice—once under Henry VII and Henry VIII from 1499-1547, and again under Mary I and Elizabeth I from 1554-1562.

Elizabeth I granted the castle to Ambrose Dudley, an elder brother of her court favorite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, whose effigy lies in nearby Collegiate Church of St Mary’s in Warwick.

But it was not until the 1740s under Francis Greville that a long 50-year period of major works changed Warwick Castle into what we know and love today.

Greville commissioned the famous Italian painter Canaletto to paint five views of Warwick Castle during the 1740s and 1750s.

“England’s greatest gardener” Capability Brown was also hired by Greville to landscape the beautiful grounds.

Remembered as “the last of the great English 18th century artists to be accorded his due”, Capability Brown designed over 170 parks, earning him the nickname “Capability” because he always saw room for improvement.

Covering over 690 acres, Greville spent the equivalent of £280,000 ($360,000) on the gardens alone.

Another famous owner was Francis Greville, 5th Earl of Warwick, but more so for his wife than anything he did.

Daisy Greville, Countess of Warwick was a campaigning socialite by day, who supported many schemes to aid the less well off in education, housing, employment and pay.

By night, she was a mistress of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, who later became King Edward VII.

Her youngest two children were reputedly fathered by a millionaire lover.

So popular was she with the public, that the music hall song “Daisy Bell” was named after her.

Give me your answer, do.

I’m half crazy

all for the love of you

Retiring to Rome and Switzerland, the last owner, David Robin Francis Guy Greville, 8th Earl of Warwick, sold Warwick Castle to The Tussauds Group for £1.3 million in 1978.

Now part of Merlin Entertainments, the world’s second largest leisure group after Disney, Warwick Castle has received many accolades, including being recognized as Britain’s best castle by the Good Britain Guide 2003.

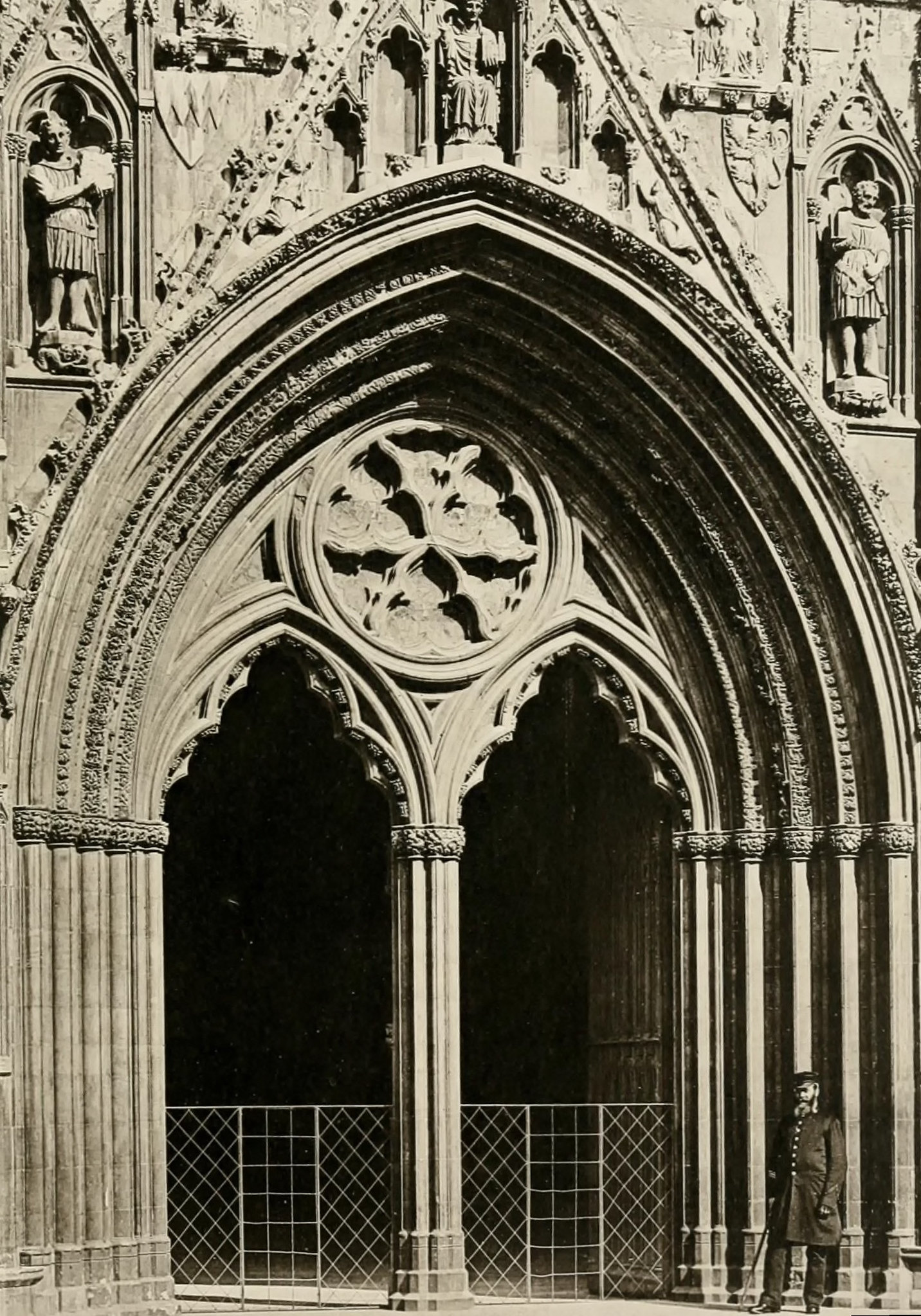

Join us as we enter Warwick Castle, the finest medieval castle in England.

Please tip the gatekeeper—wonderful fellow once you get to know him, but please try not to upset him.

Inside Warwick Castle

Who needs Netflix when you have live entertainment at home?

Lady Warwick (Daisy Greville) was a favourite of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales and entertained him and his entourage lavishly.

She and her husband were members of the Marlborough House Set, headed by the Prince of Wales (the future Edward VII).

When one was a favourite of the future king, their friends would “prove their worth” through favours.

Cecil Rhodes, a good friend of Lady Warwick, made sure that her investments in South Africa were successful.

You look beautiful ma’am, do excuse me while I change the baby for a cleaner one.

Third Class Accommodations

If you misbehaved at dinner, you may find yourself in third class accommodations deep in the bowels of Warwick Castle, i.e. the dungeons.

In the Middle Ages, a variety of devices were used on unwelcome guests to exploit their sensitivities to pain and glean confesssions and other useless bits of information.

And if they were really lucky, they could spend the night in the gibbet.

The Glorious Grounds

Who said Chivalry was dead?

The collection of armoury on display at Warwick Castle is regarded as second only to that of the Tower of London.

Qu’est-ce que c’est, un trebuchet?

Warwick Castle is home to one of the world’s most powerful siege engine.

At 59 ft tall, the trebuchet is made from over 300 pieces of oak and weighs 24 tons.

Taking eight men half an hour to load and release, the trebuchet can hurl projectiles of up to 330 lb distances of almost 1000 ft and as high as 82 ft at a speed of over 120 mph.

Water Mill and Mill Garden

A water-powered mill in the castle grounds was probably built under Henry de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Warwick.

Adjacent to the mill is The Mill Garden which is privately owned but open to the public. Interesting views of the castle can be seen from this garden.

The Old Castle Bridge

A day well spent!

As the light starts to dim over Warwick Castle, you will be reminded that time flies when you’re having fun.

A day to remember for a lifetime.