Stately Homes are large mansions set in the English countryside, typically owned by the British nobility or the landed gentry of the upper class.

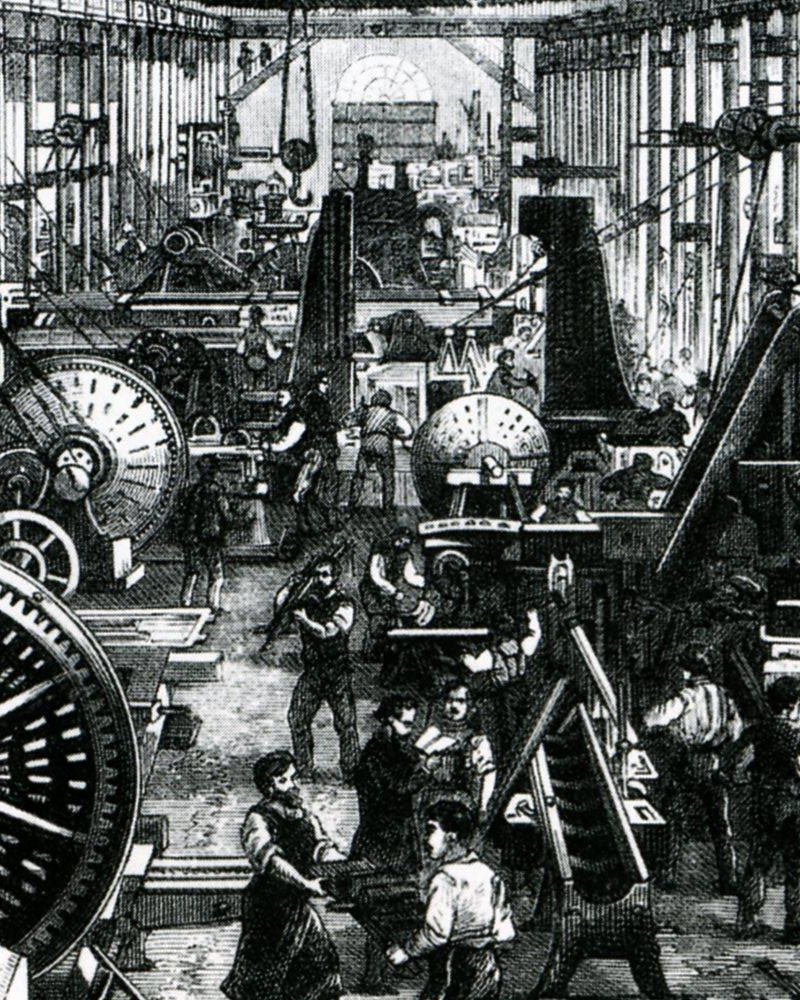

Important as places of employment for many rural communities, large numbers of indoor and outdoor staff catered to every need of the owners who traveled frequently between homes in the city and the country.

After World War I, increased taxation and the loss of family fortunes led to the demolition of hundreds of houses, with those that remained, struggling to survive.

Here are 10 examples of Stately Homes in beautiful condition that are open to the public.

Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire

Built between 1705 and 1733, Blenheim Palace was originally a gift from Queen Anne to John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough for his victory over the French in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 – 1714).

Before Blenheim Palace was even completed, political intrigue between Marlborough’s wife and Queen Anne forced the Duke and Duchess to leave the country in disgrace.

Returning to England on the day of the queen’s death, the Marlboroughs regained royal favour under King George I and moved into Blenheim Palace in 1719.

Designed in the rare, and short-lived, English Baroque style, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the only non-royal non-episcopal stately home in England to hold the title of palace.

Born at Blenheim Palace on 30 November 1874, Sir Winston Churchill was a direct descendant of the Dukes of Marlborough.

One of England’s largest stately homes, Blenheim was saved from ruin in the late 19th century with funding from American railroad heiress Consuelo Vanderbilt upon her marriage to the 9th Duke of Marlborough.

Burghley House, Cambridgeshire

Reflecting the prominence of its founder, William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley and chief advisor to Queen Elizabeth I for most of her reign, Burghley House is one of the leading examples of 16th-century English Elizabethan architecture.

Featured in several period movies, including Pride and Prejudice and The Da Vinci Code, its virtually unaltered Elizabethan facades and historic interiors make it an ideal location for filming.

Famed 18th-century English landscape architect Capability Brown laid out the parkland avenues and 26-acre man-made lake.

Created using traditional ideas of water traps, shell grottos, and a mirror maze in a 21st-century style, the “garden of surprises” was added in 2007.

Known as “prodigy houses”, these extravagant palaces were often built by courtiers and other wealthy families to house Elizabeth I and her retinue as she traveled around her realm.

With 35 major rooms on the ground and first floors, there are over 80 lesser rooms and numerous halls, corridors, bathrooms, and service areas.

Castle Howard, North Yorkshire

Beginning in 1699, Castle Howard would take over 100 years to complete, becoming the home of the Carlisle branch of the noble Howard family.

Descended from the third son of Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk (executed by Queen Elizabeth I in 1572), the Earls of Carlisle have been seated at Castle Howard for over 300 years.

Although not a true castle, the term is often used to describe stately homes built on sites of former military fortresses.

Dominating the fountain in Castle Howard’s grounds is a large bronze globe supported on the shoulders of the figure of Atlas from Greek mythology.

Added to the design at a late stage, the crowning central dome epitomizes the rich decorative Baroque architecture so beloved by the architect and English playwright Sir John Vanbrugh.

With a total of 145 rooms, Castle Howard is one of the largest stately homes in England.

Chatsworth House, Derbyshire

Often selected as Britain’s favourite stately home, Chatsworth House sits on the banks of the River Derwent within the beautiful hills and valleys of the Derbyshire Dales.

Set in expansive parkland and backed by wooded hills, the house contains an important collection of paintings, furniture, and neoclassical sculptures.

The seat of the Duke of Devonshire, Chatsworth House has been home to the Cavendish family, one of the richest British aristocratic families, since the 16th century.

Anticipating a visit from Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, the 6th Duke constructed an eight-acre lake with the world’s highest fountain reaching almost 300ft.

Decorated with murals from the life of Julius Caesar by French painter Louis Laguerre, the cantilevered Great Stairs lead to a suite of richly appointed staterooms built in anticipation of a royal visit by King William III and Queen Mary that never took place.

Harewood House, West Yorkshire

Employing the finest craftsmen of the day—architect John Carr, interior designer Robert Adam, furniture maker Thomas Chippendale, and landscape gardener Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown—Edwin Lascelles, 1st Baron Harewood wanted nothing but the best for his new home, Harewood House.

Laying the foundations in 1759, the house was largely complete within six years.

Filled with renaissance masterpieces, exquisite portraits by Reynolds, Gainsborough, Lawrence, and Richmond, and a fine collection of Sèvres French porcelain, Harewood House has featured in both television and film.

Used as a filming set for the TV Series “Victoria”, the gallery and other rooms display some of the costumes used in the show.

Running through the design theme of the Yellow Room is Robert Adam’s meticulous attention to detail.

Echoed in the ceiling, without being a direct copy, he repeats the star and circle motifs of the carpet, and around the frieze and doorways, he repeats the plaques with cupids and seahorses.

Hatfield House, Hertfordshire

Set in extensive parkland and manicured gardens, Hatfield House is a leading example of a Jacobean prodigy house—a large and showy stately home built to accommodate Queen Elizabeth I and her entourage as they toured her realm.

It is here, in 1558, while sitting under an oak tree in the Park of the Old Palace, that Elizabeth first learned of her succession to the throne.

In 1607, King James I gave the original Old Palace to his chief minister Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, in exchange for Cecil’s family estate at Theobalds.

Tearing down three wings and using the bricks to build the present structure, Cecil spared no expense to create an opulent home furnished with fine art and tapestries fit for royal visits.

Hatfield’s showpiece Marble Hall, with its signature black and white marble floor, features the famous Rainbow Portrait, depicting Elizabeth as the “Queen of Love and Beauty”.

Gloriana! The many faces of Queen Elizabeth I.

Running 170ft along the width of the south front is the Long Gallery housing some clothing items belonging to Elizabeth, including a hat, some gloves, and silk stockings thought to be the first pair in England.

Longleat House, Wiltshire

Noted for its architecture, landscaped parkland, and more recently, a maze, and safari park, Longleat is another example of a prodigy house built by wealthy families to entertain Elizabeth I and her retinue on their royal visits.

Regarded as one of the finest examples of Elizabethan architecture in Britain, it was built by Sir John Thynne, steward to the 1st Duke of Somerset, and designed by master stonemason Robert Smythson.

Set in 1000 acres of parkland designed by the 18th century’s leading gardener Lancelot “Capability” Brown, Longleat was the first stately home to open to the public and the first safari park outside of Africa.

Inspired by estates in Genoa and Venice, the interior decoration includes superb Flemish tapestries, 16th-century fine art, and period furniture.

Formerly called the Long Gallery, the 90ft Saloon features a huge Carrara marble fireplace and beautiful coffered ceiling.

Petworth House, West Sussex

Once owned by the Percy family who held the peerage title Earls of Northumberland, Petworth is a 17th-century baroque stately home set in a sprawling 700-acre landscaped deer park designed by Capability Brown.

Intended as an occasional second home to their primary seat at Alnwick Castle in Northumberland that borders Scotland, the Percy’s were forced to make Petworth their main residence on the orders of Queen Elizabeth I who suspected the family’s allegiance to Mary, Queen of Scots.

Housing an important collection of paintings and sculptures, the Petworth collection includes 19 oil paintings by J. M. W. Turner, who was a regular visitor, and paintings by Anthony van Dyck as well as sculptures and carvings by Grinling Gibbons.

Decorated with a magnificent series of allegorical murals by renowned French painter Louis Laguerre (1663 – 1721), the Grand Staircase also depicts the story of Lady Elizabeth Percy who, as a two-year-old, inherited four vast estates, including Petworth from the 11th Earl of Northumberland when he died without a male heir.

Stowe House, Buckinghamshire

Dating back to the 16th century when the Temple family bought the manor and estate of Stowe, the house was completely rebuilt in the 17th century and has subsequently been extended three more times over the years to create the 916-foot facade of today.

Considered one of the finest examples of neoclassical architecture in Britain, the south face was designed by Robert Adam and Thomas Pitt, both involved at the highest levels of 18th-century architecture.

Exquisitely decorated by Italian artist and architect Vincenzo Valdrè, the paintings of the elegant Music Room were inspired by those seen on a visit to Pompeii by the 1st Marquess of Buckingham, owner of Stowe from 1779-1813.

The plaster ceiling has gilt molded decoration and seven inset paintings with the central circular painting of The Dance of the Hours after Guido Reni and flanked by rectangular paintings of the four seasons.

Created in three main phases, the landscaped gardens of Stowe were worked on by William Kent who, together with Charles Bridgeman, originated the naturalistic landscape style, and Capability Brown, who became known as “England’s greatest gardener”.

Completed in 1738, the Palladian Bridge was copied from the bridge at Wilton House in Wiltshire but was designed with ramps instead of steps to allow horse-drawn carriages to cross.

Waddesdon Manor, Buckinghamshire

Built between 1874 and 1889 in the Neo-Renaissance style of a French château, Waddesdon Manor was a weekend residence of Baron Ferdinand de Rothschild for grand entertaining and to store his art collection.

Embodying an eclectic style based on the châteaux of the Loire Valley, the towers were inspired by those of the Château de Maintenon and the twin staircase towers are based on the staircase tower at the Château de Chambord.

Laid out by French landscape architect Elie Lainé, the gardens at Waddesdon were an important part of Baron Ferdinand’s many weekend house parties.

Planting nearly 19,000 flowers and bulbs each year, the parterre is the formal garden consisting of beds laid out in symmetrical patterns.

Waddesdon’s rooms are exquisitely decorated and filled with English 18th-century portraits by Gainsborough and Reynolds, as well as French 18th-century carpets, tapestries, furniture, and ceramics.

Designed for after-dinner entertainment, the Grey Drawing Room features fine 18th-century French carved paneling, Sèvres porcelain, and three portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds.